I am writing this as a reminder to myself and to colleagues.

Total Float is NOT schedule contingency. That’s right: Total Float is NOT schedule contingency. I say this after the umpteenth conversation with a very smart and experienced contractor who regularly uses the terms interchangeably.

First, a couple references:

Merriam-Webster

Merriam-Webster defines “contingency” as a Noun thus:

1: a contingent event or condition: such as

a: an event (such as an emergency) that may but is not certain to occur

b: something liable to happen as an adjunct to or result of something else

2: the quality or state of being contingent

When budgeting projects, our usage of the term has evolved from an “allowance for contingencies”, through “contingency account”, to often a simple “contingency” amount – setting aside funds for uncertain costs or unknown risks in project scopes. Similarly, a “schedule contingency” exists as an explicit setting-aside of time to address uncertain durations or risks in project schedules.

AACE

AACE International (formerly the Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering International) issued a Recommended Practice for Schedule Contingency Management (70R-12) that defines schedule contingency as, “an amount of time included in the project or program schedule to mitigate (dampen/buffer) the effects of risks or uncertainties identified or associated with specific elements of the project schedule.” Then the RP emphasizes, “Schedule contingency is not float (i.e. neither project float* nor total float).” Finally, the RP goes on to define Project Float (in a footnote) as, “the length of time between the contractor’s forecast early completion and the contract required completion.” A key theme of the recommended practice is to make schedule buffers explicit, visible, and allocated to specifically identified schedule risks.

* I might quibble with the “project float” exclusion, particularly in any case where risk mitigation is its primary motivation.

ASCE

The American Society of Civil Engineers recently published a new standard: ANSI/ASCE/CI 67-17 – Schedule Delay Analysis. Page 5 of this new standard provides a fairly long definition of “Float” that seems essentially correct with the pronounced exception of its first clause, “Float — The time contingency that exists on a path of activities.” Obviously, this is a direct contradiction to the AACE definition above. It also appears largely at odds with the rest of the definition in the ASCE standard.

DCMA

The Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) promulgated a 14-Point Assessment methodology for analysis of Integrated Master Schedules, which seems to have been widely adopted in some industries.

Point 13 of the DCMA’s 14-Point Analysis defines the Critical Path Length Index (CPLI) as:

Critical Path Length + Total Float

CPLI = ____________________________________

Critical Path Length

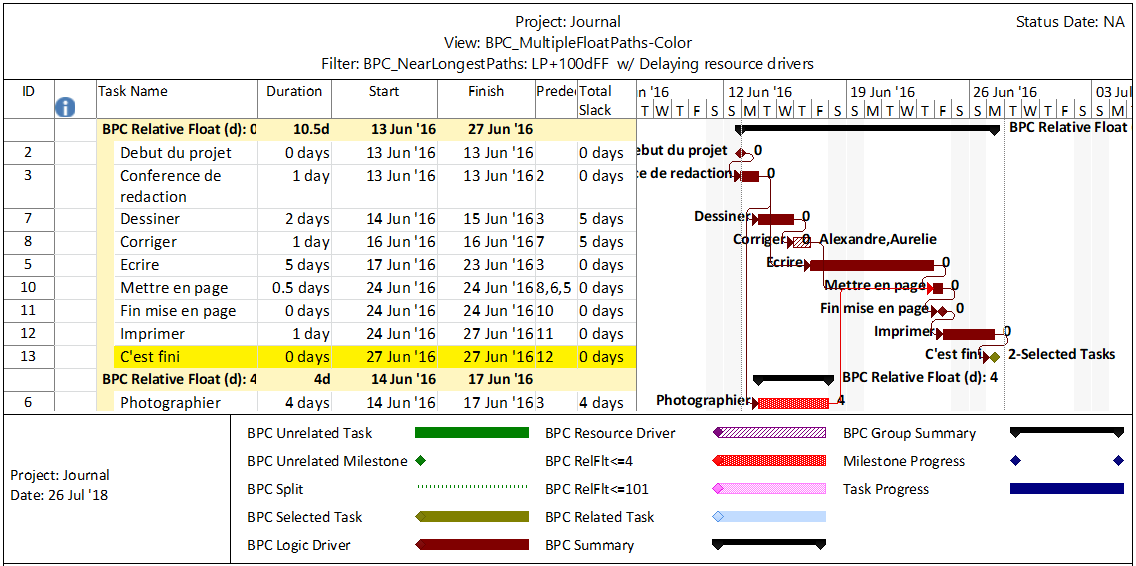

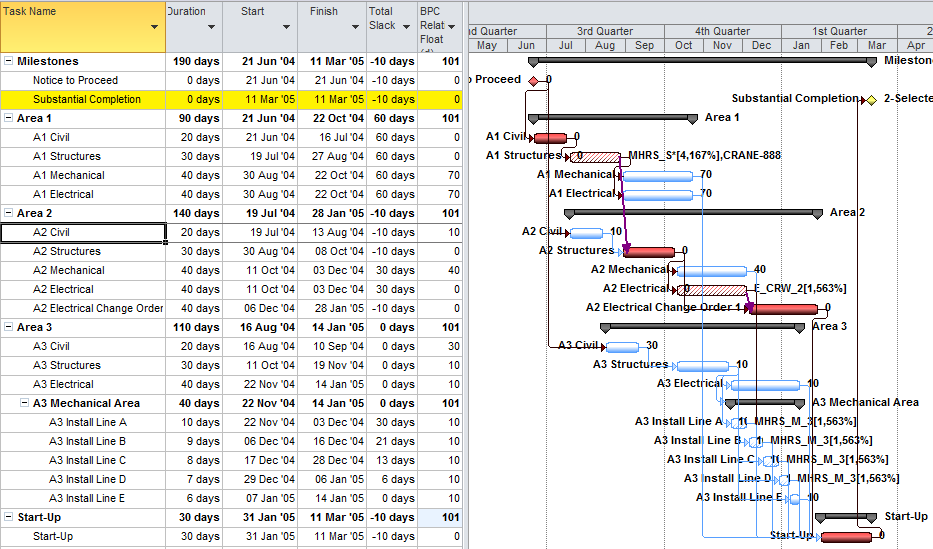

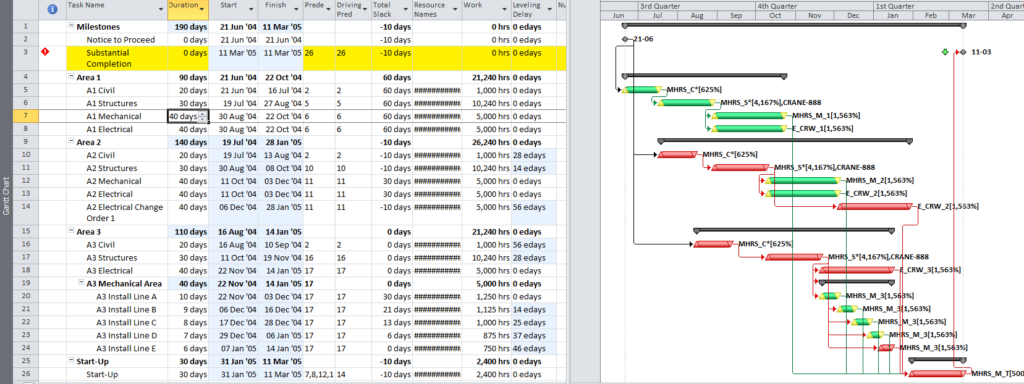

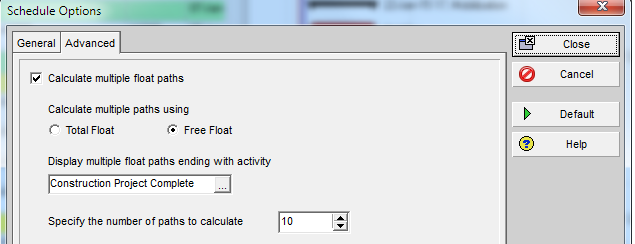

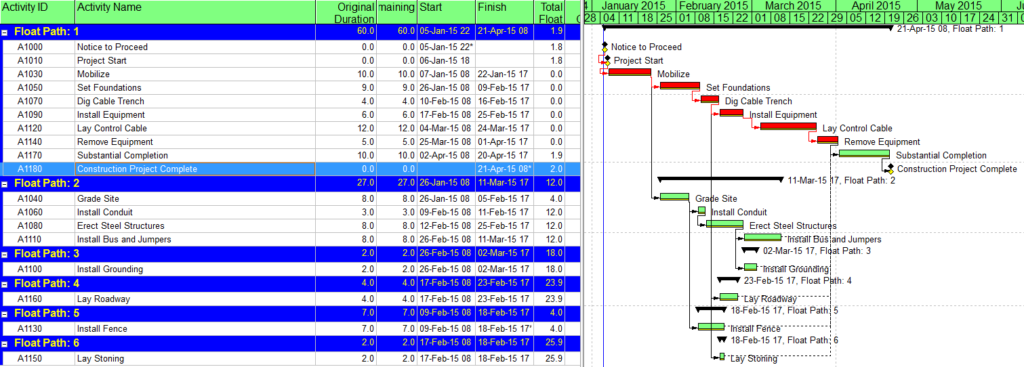

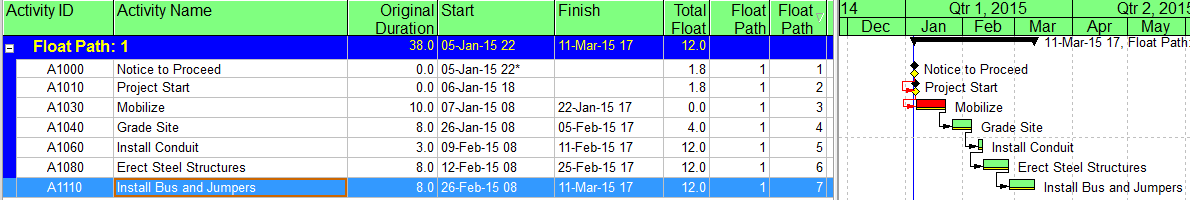

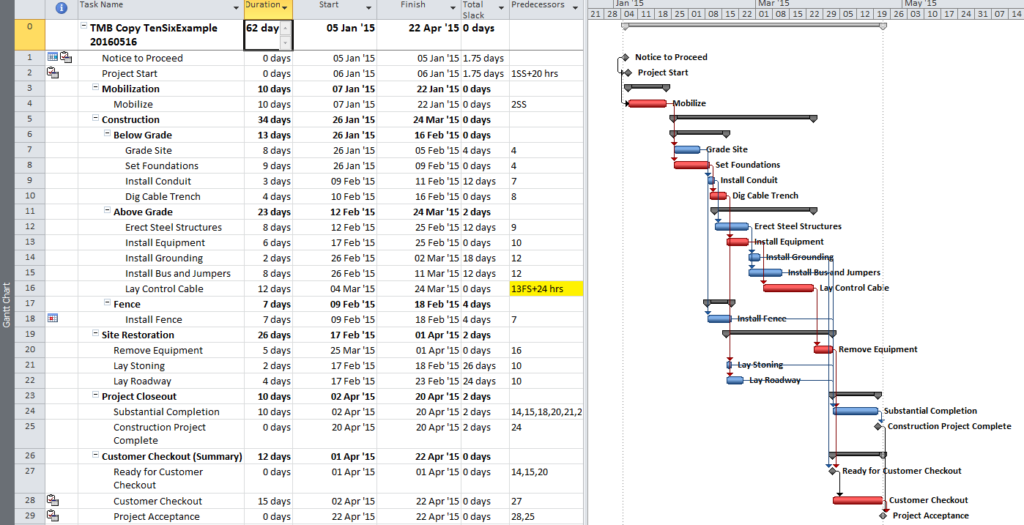

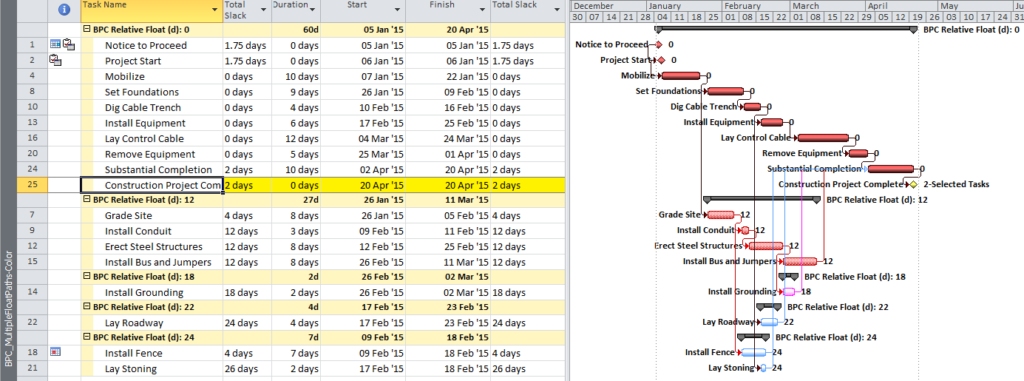

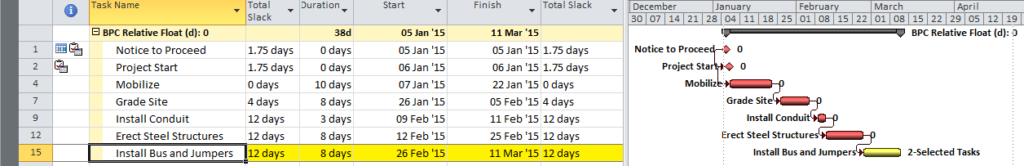

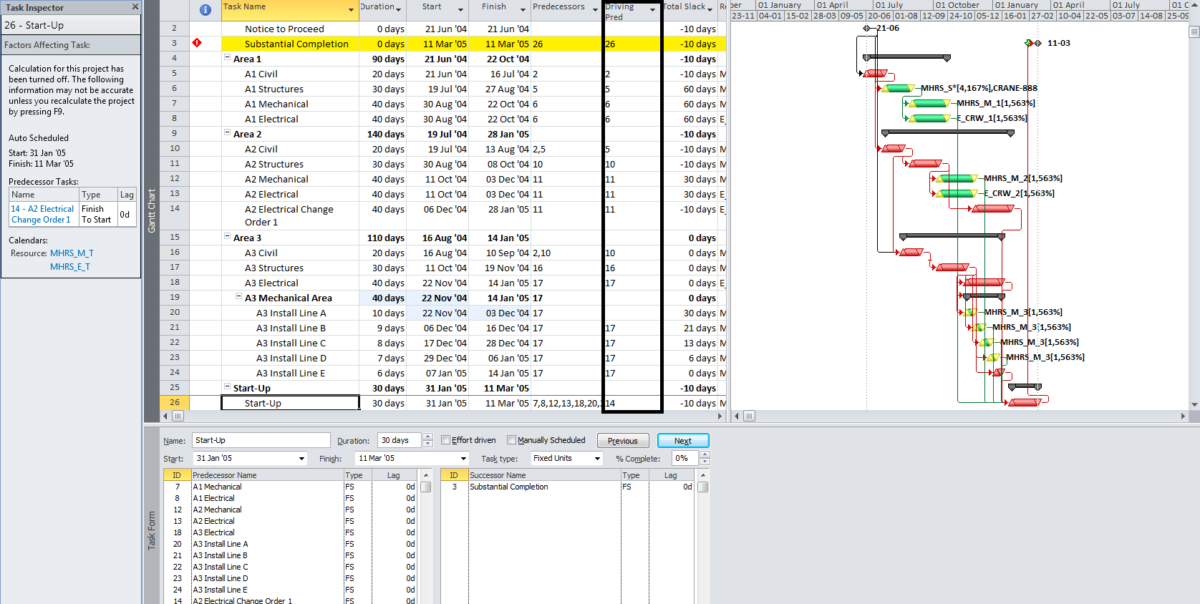

Here the “Critical Path Length” is essentially the time (in days) from the current data/status date until the forecast completion date of the project. The “Total Float” used in the ratio turns out to be the difference between the forecast completion date and the baseline/contract completion date – we otherwise know this as “Project Float.” (This is also the value of Total Float that Oracle’s Primavera P6 scheduling software displays on the Critical Path when a Project “must finish by” constraint corresponding to the contract completion date is assigned.)

The DCMA guidance provides a target value of 1.00, corresponding to a Project Float of 0. It goes on to suggest that a CPLI greater than 1.00 (i.e. Project Float is positive) is favorable while a CPLI less than 1.00 (i.e. Project Float is negative) is unfavorable.

NEC ECC

The NEC Engineering and Construction Contract (ECC), a collaborative contract form with increasing use in UK and Commonwealth countries, has formalized the use of two alternate terms for schedule contingencies:

Terminal Float

Terminal Float is the difference between the current Planned Completion date and the (Contract) Completion Date. It is not of a fixed size, is not allocated to any particular risk(s), and is reserved for the exclusive use of the Contractor. Notably, an acceleration of early activities that results in acceleration of the Planned Completion date also increases the Terminal Float. Terminal Float is equivalent to the Project Float of AACE International terminology.

Time Risk Allowance

Time Risk Allowance (TRA) “is made by the contractor when preparing its programme. These are owned by the contractor and provided to demonstrate that the contractor has made due allowance for risks which are the contractor’s under the contract. They must be realistic – unrealistic allowances could prevent the project manager from accepting the programme.” In other words, TRA is explicit time contingency buffer/allowance that is allocated to specific activities and risk events in the project schedule.

Clause 31 of the NEC Engineering and Construction Contract (ECC) requires the Contractor to show float and “time risk allowance” (TRA) on the programme (i.e. schedule). The NEC does not specify exactly how to “show” the TRA, though the demand that it be “realistic” has been used to justify a requirement that TRA be distributed through the project schedule based on explicit risk assessment (like the AACE RP). Typically, the TRA is included in padded activity durations, with the specific TRA portion explicitly noted in a custom field for each activity. In any case, the TRA participates directly (as a duration) in the CPM calculations for the deterministic project schedule, an output of which is Float. (Obviously, it must be excluded from any schedule risk simulations.)

Confusion

The mixed definitions have led to some confusion and contradictory recommendations from professionals.

The ASCE document on Schedule Delay Analysis implies that “time contingency” simply exists, manifested as Float, on a network path. This is far from the common use of “contingency” as an explicit and proactive allowance for risk.

In the NEC environment, there seems to be a persistent tendency to conflate TRA with various types of Float, with some reputable legal sources describing both Terminal Float and “Activity” float as “leeway the contractor adds” in case of problems. In some cases, contractors are being advised to explicitly mis-identify activity Free Float as Time Risk Allowance in their project schedules, thereby reserving that portion of the activity’s Total Float for themselves.

My View:

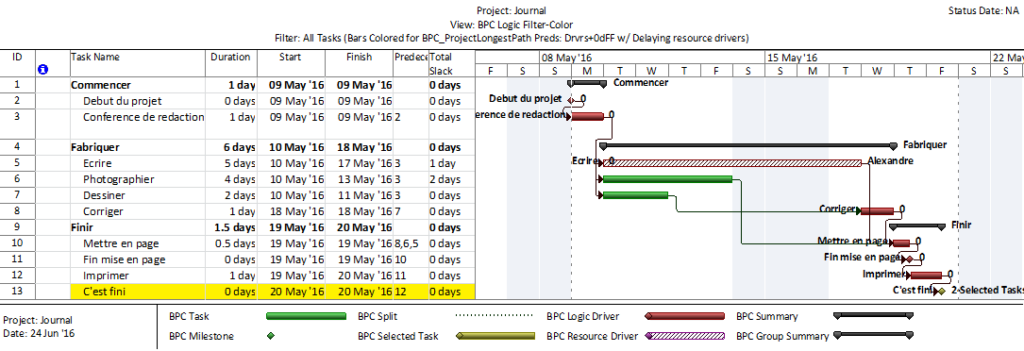

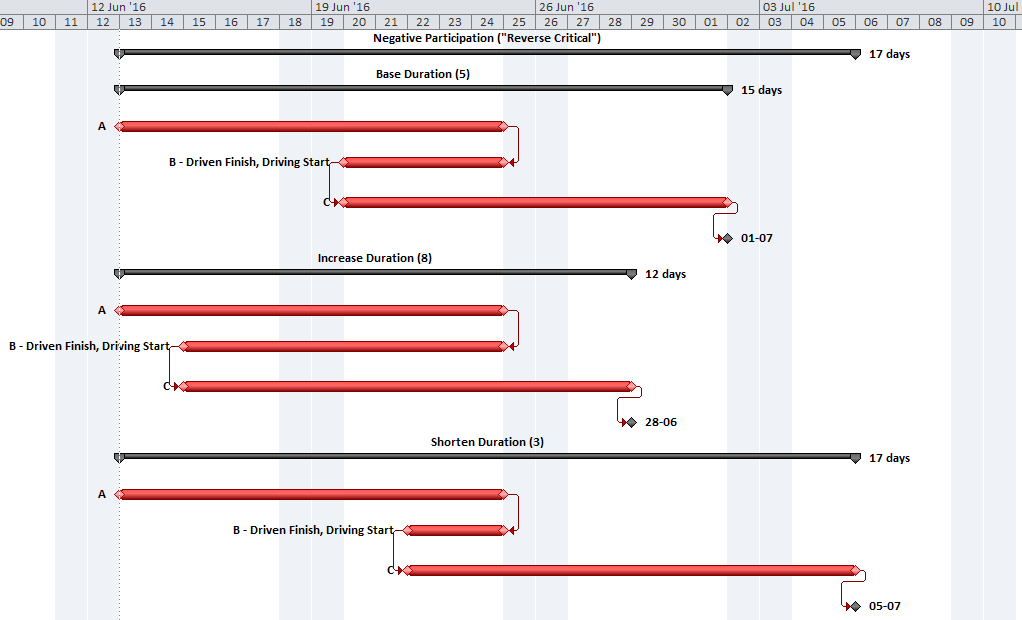

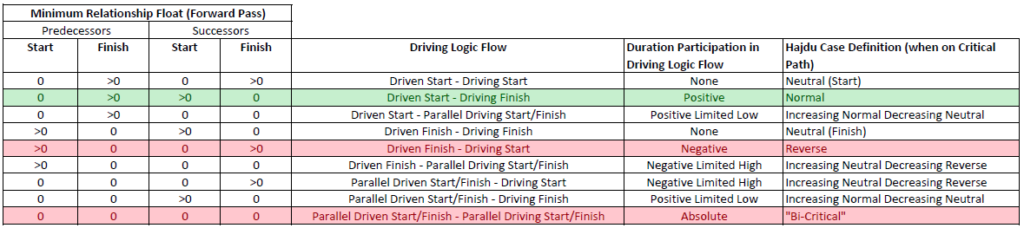

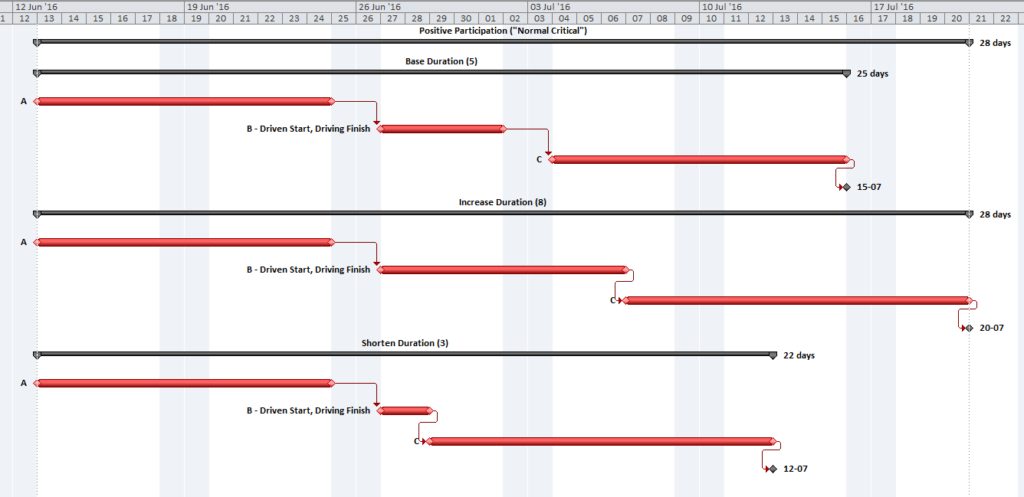

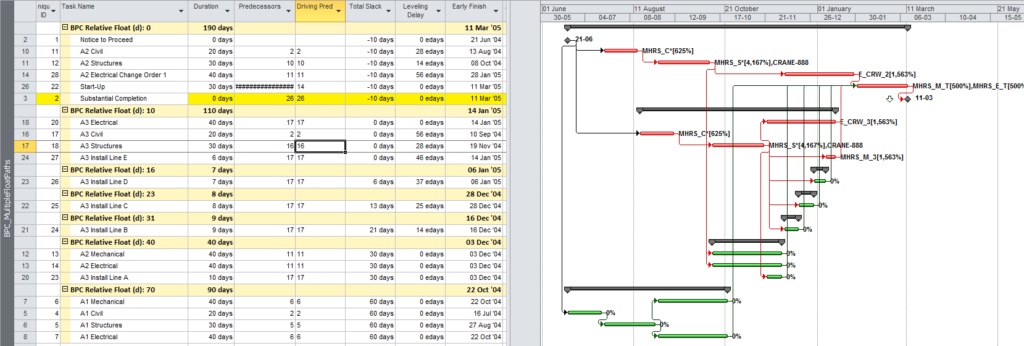

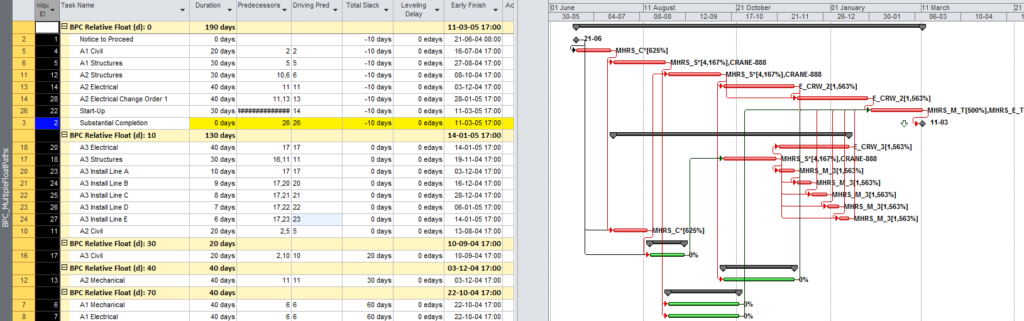

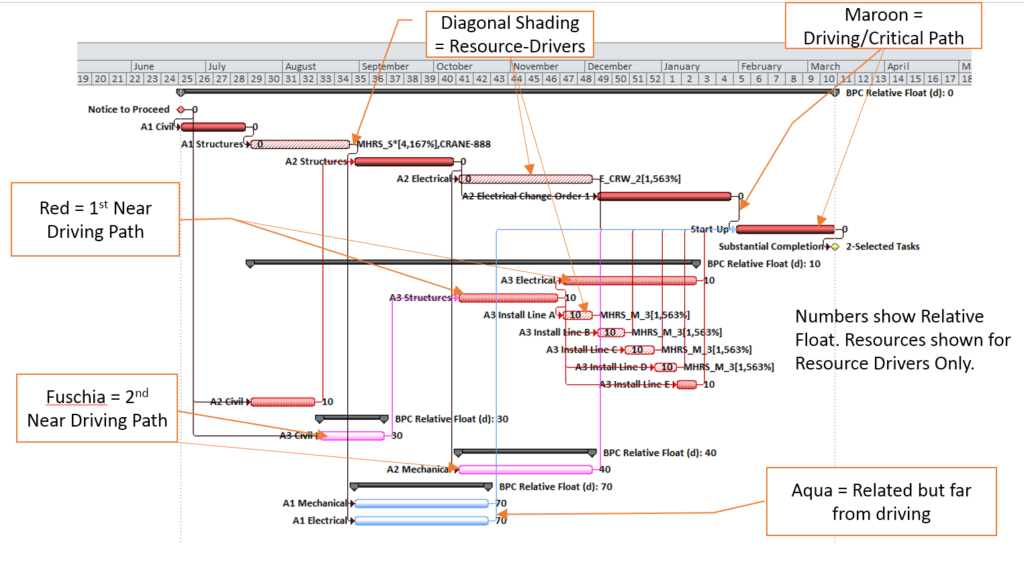

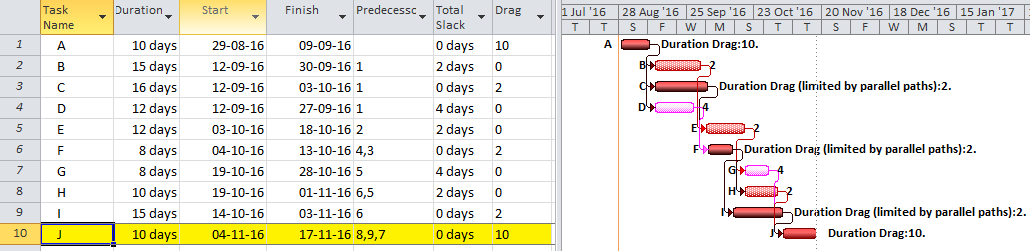

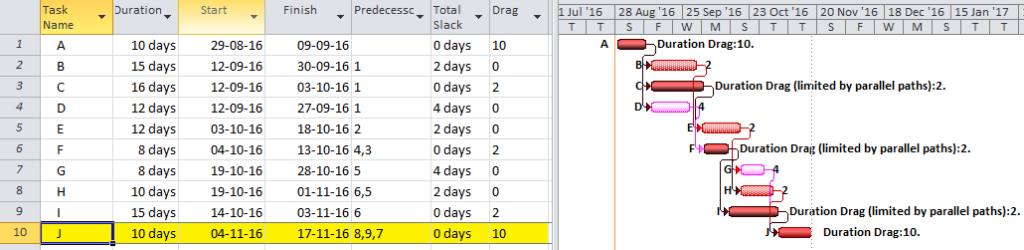

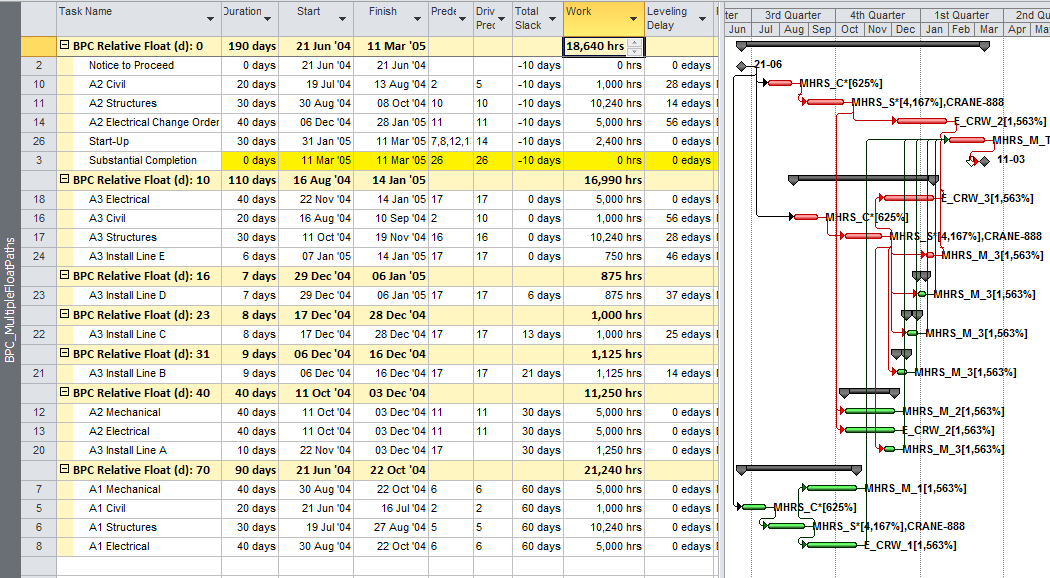

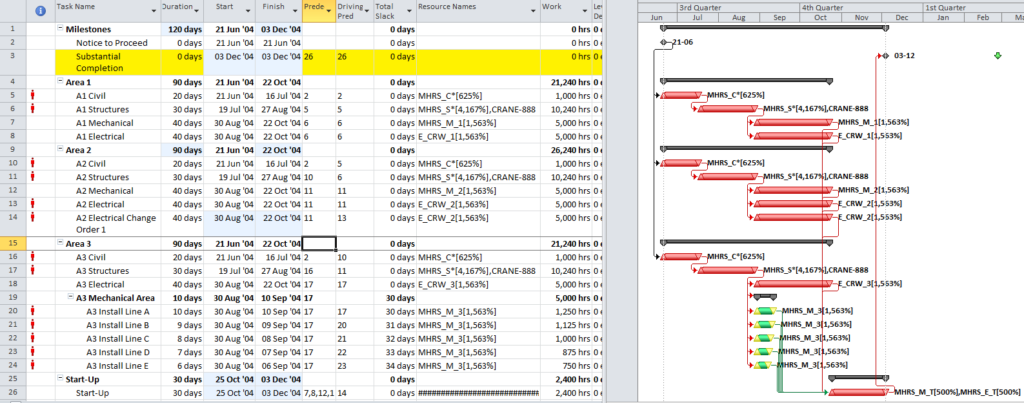

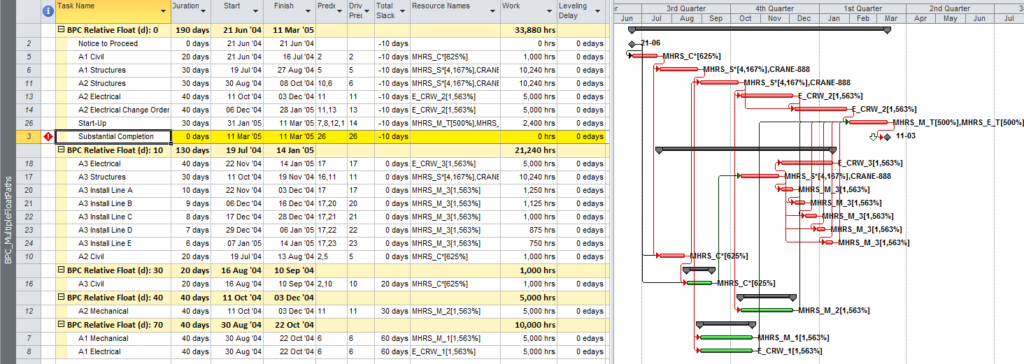

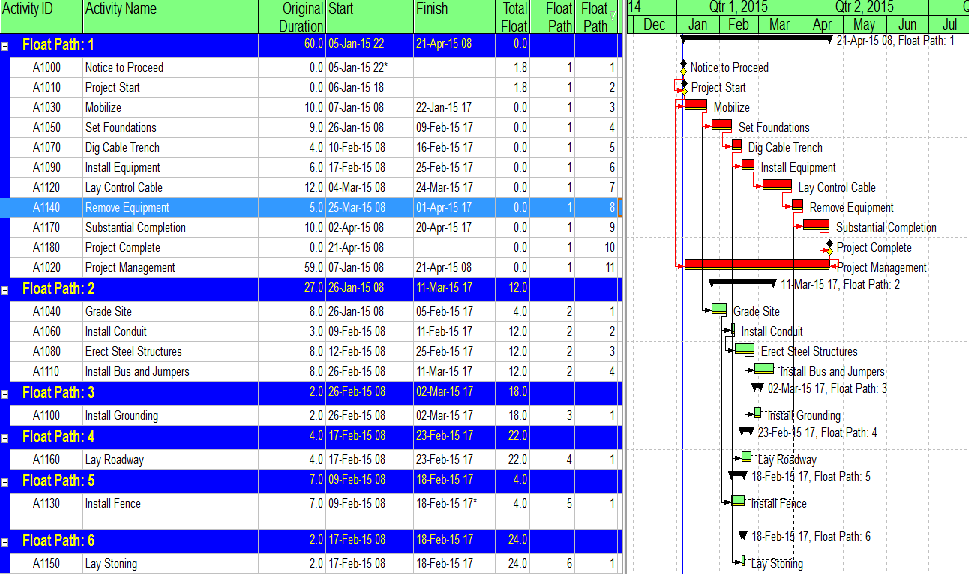

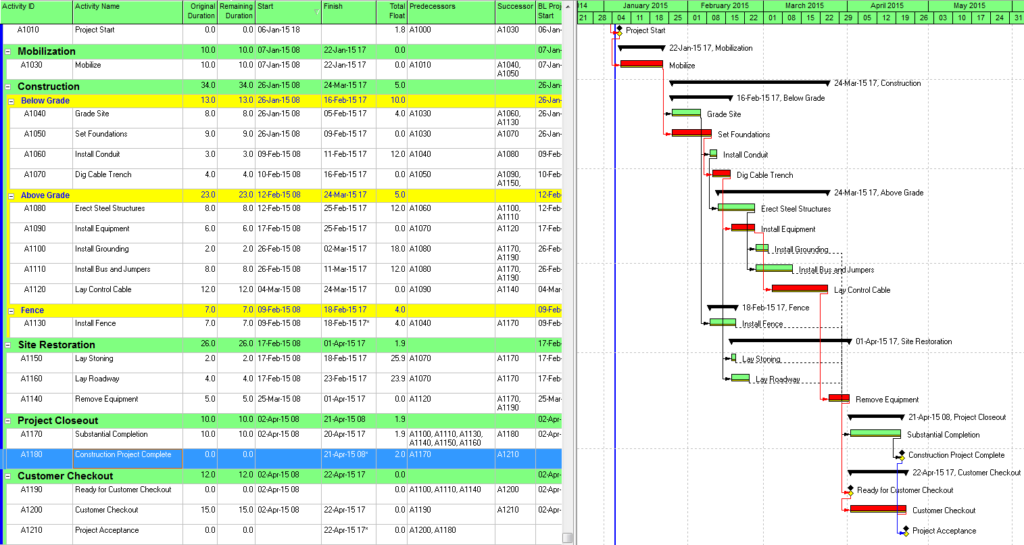

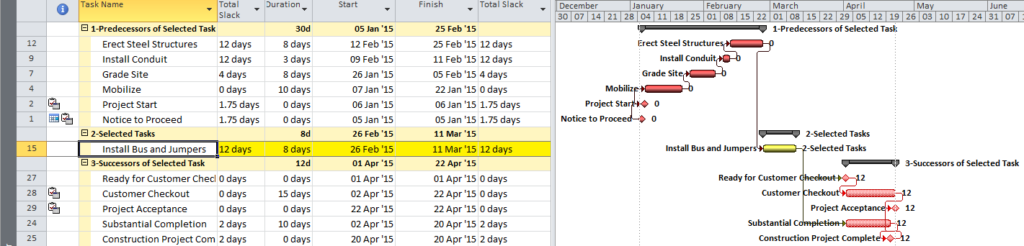

Total Float and its components, Free Float and Interfering Float, are artifacts of the Critical Path Method (CPM) for project scheduling; they are computed and applied for each individual activity in the schedule. Float essentially exists at the activity level, and its aggregation to higher levels of organization (e.g. WBS, Project, Program) is not well established.

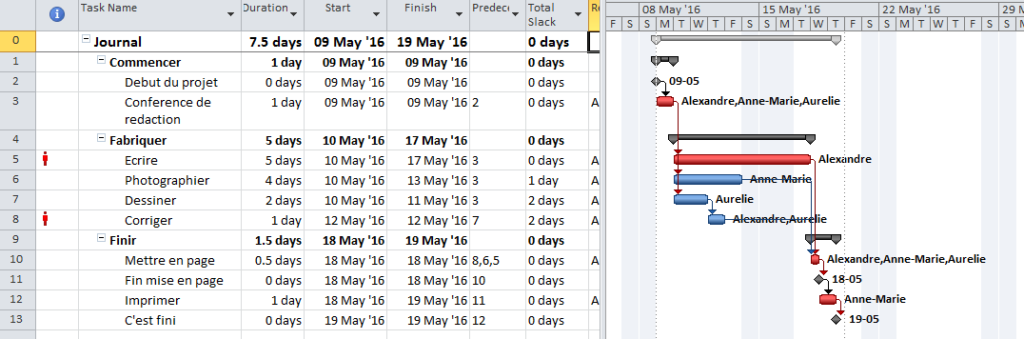

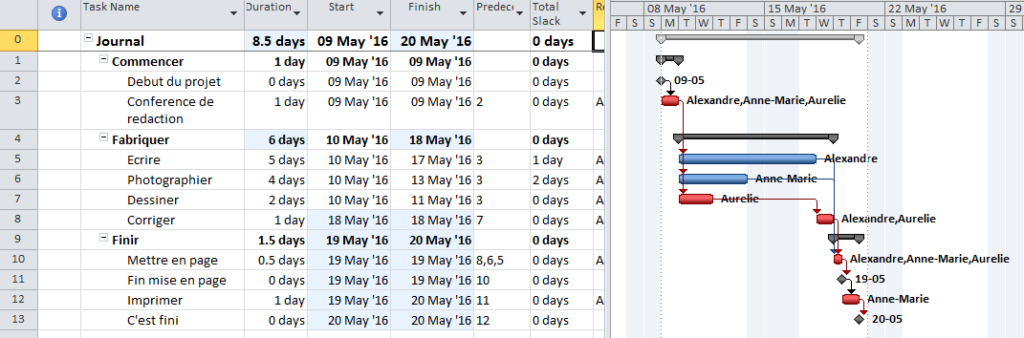

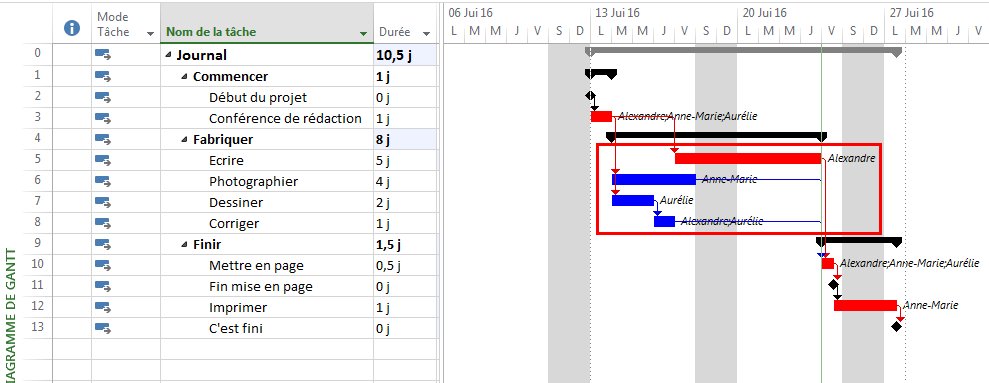

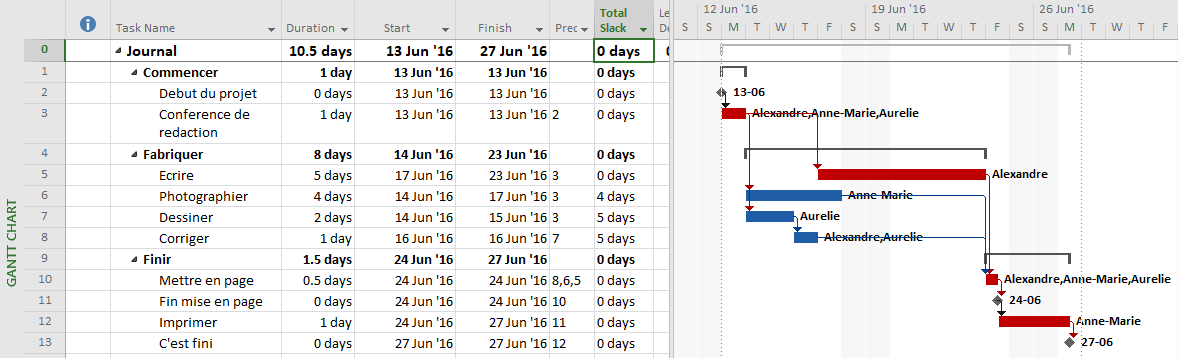

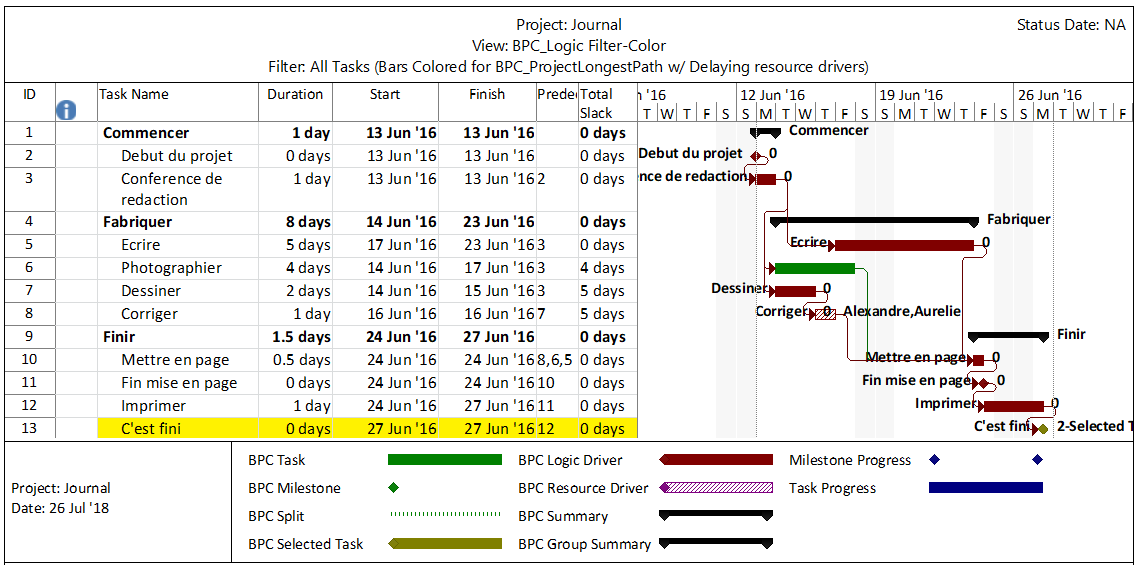

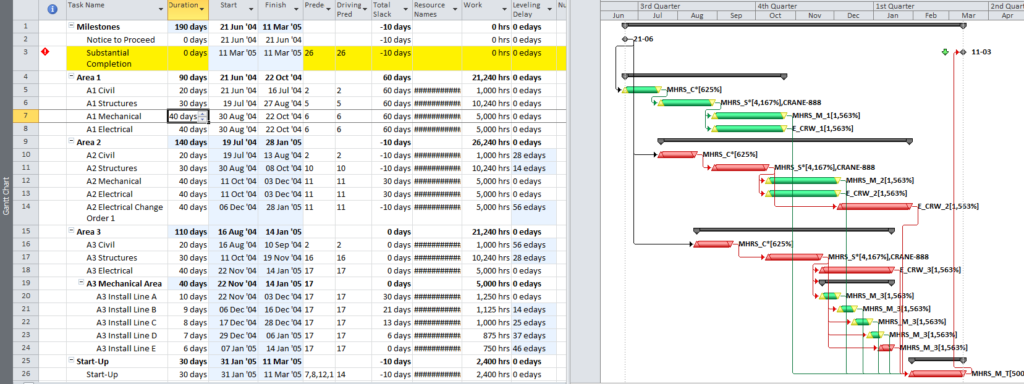

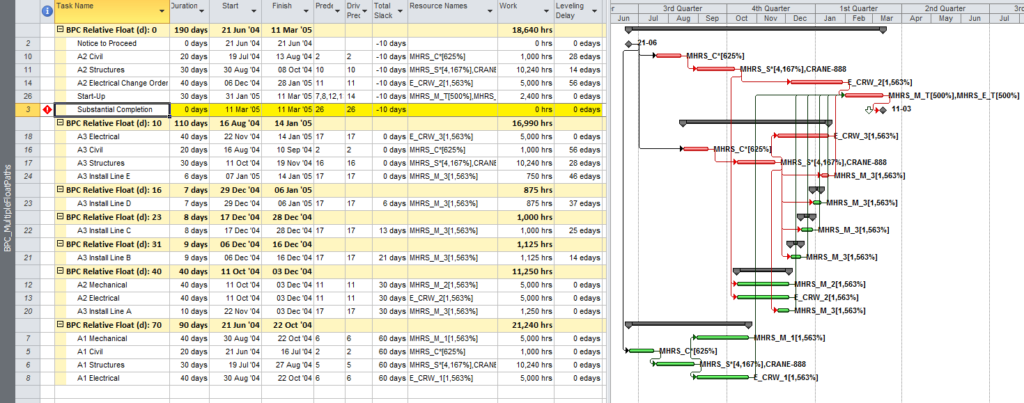

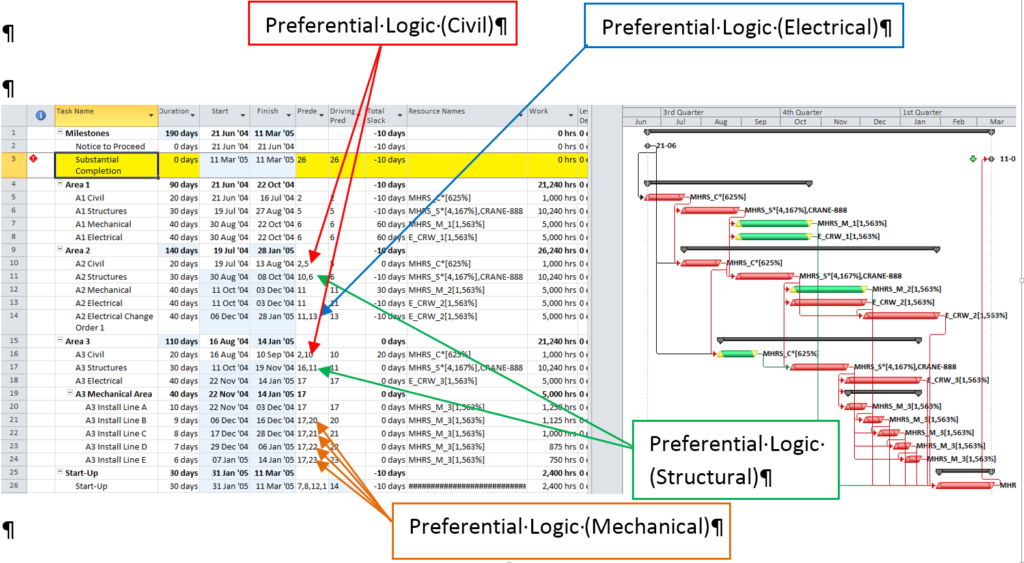

In the simplest CPM case (i.e. absent any late constraints, calendar offsets, or resource leveling), Total Float describes the amount of time that a particular activity may be delayed (according to a specific workday calendar) without delaying the overall project. The calculation is made with no concern for risk mitigation, and its result is strictly due to the logic arrangement of activities. Those activities with Total Float=0 are those for which ANY delay will cascade directly to delay of the project – this is the Critical Path. Traditionally, activities with substantial Total Float are allowed to slip as needed to divert resources to the Critical Path. This does not mitigate the overall project schedule risk, however, since the Critical Path itself is not buffered. A distinct schedule contingency/buffer to address schedule risk along the Critical Path is necessary at a minimum. Risk buffering of non-critical activities is also needed to guard against the consumption of float by outside parties. Although contractors will often provide the necessary buffers by padding activity durations, the padding is rarely identified as such (except in NEC contracts). Either explicit schedule contingency activities or explicit identification of risk buffers that are included in activity durations are preferred. Regardless of the method chosen, clearly this is not Float.

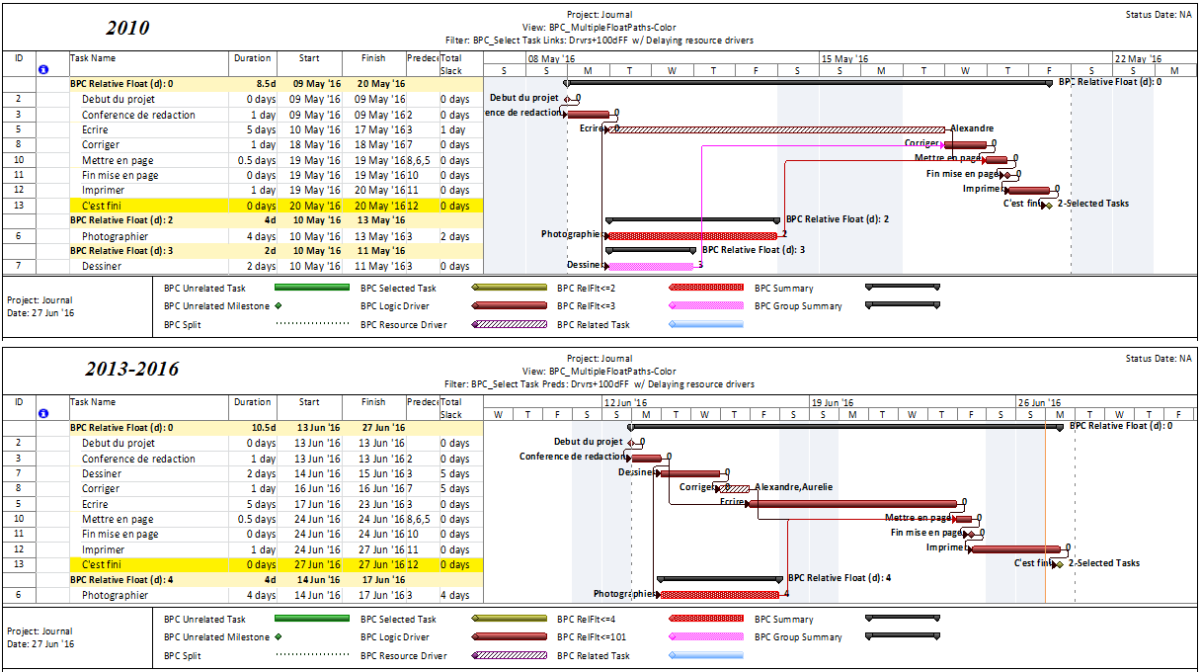

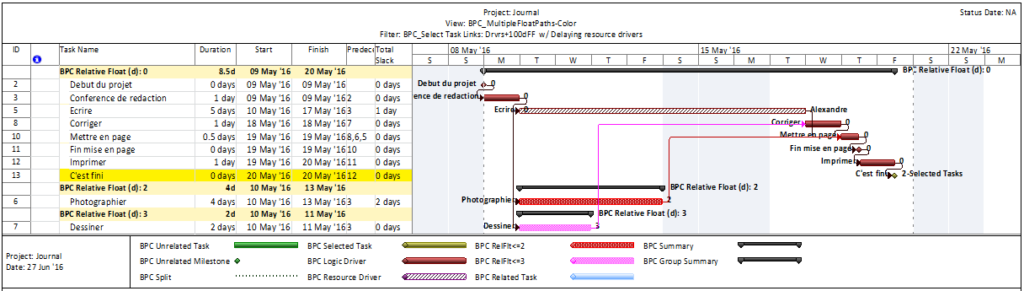

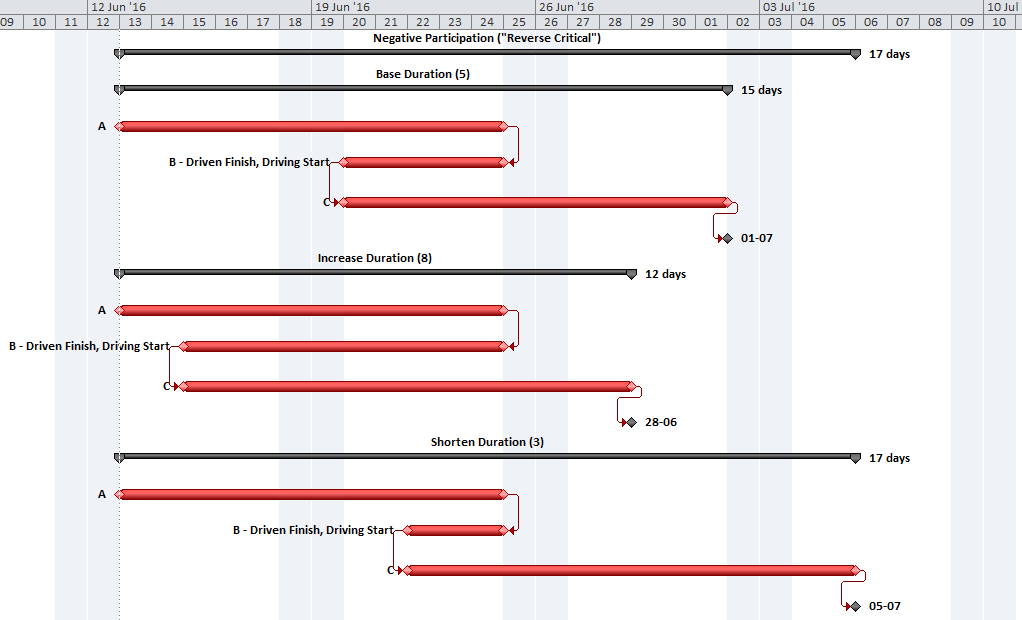

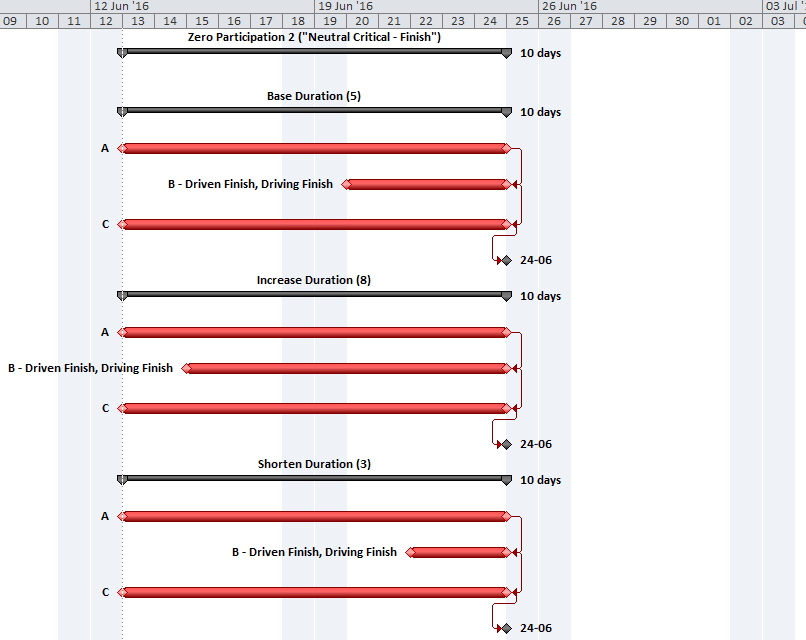

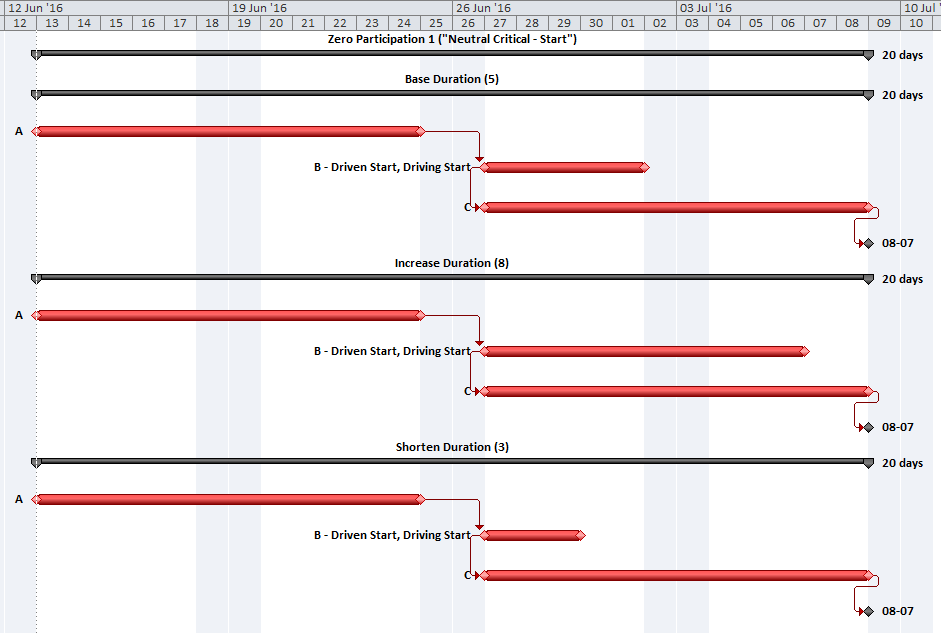

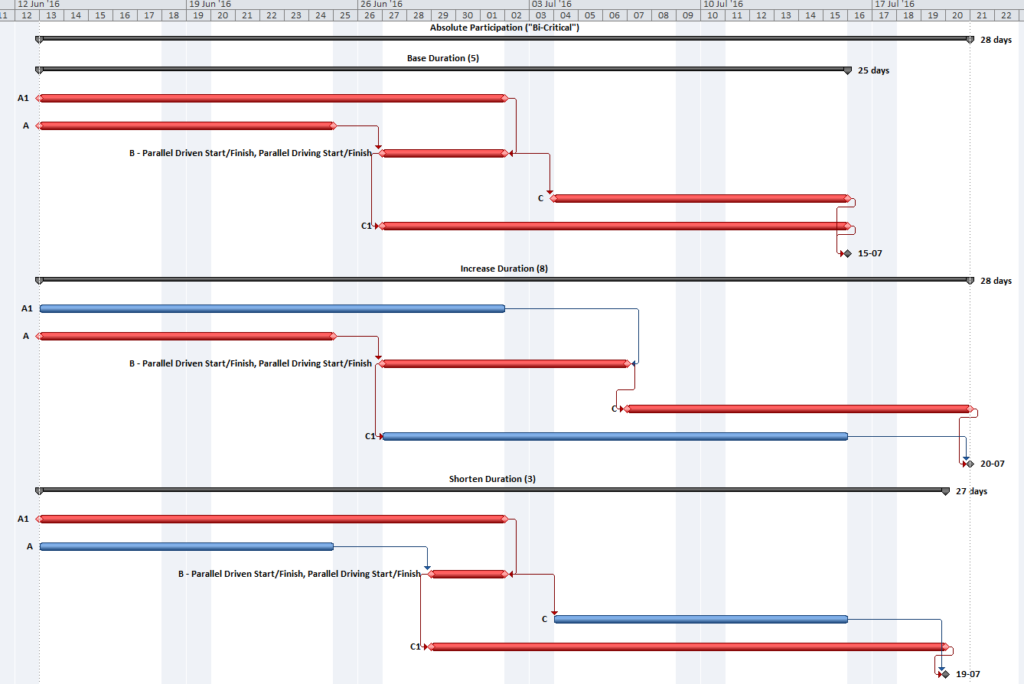

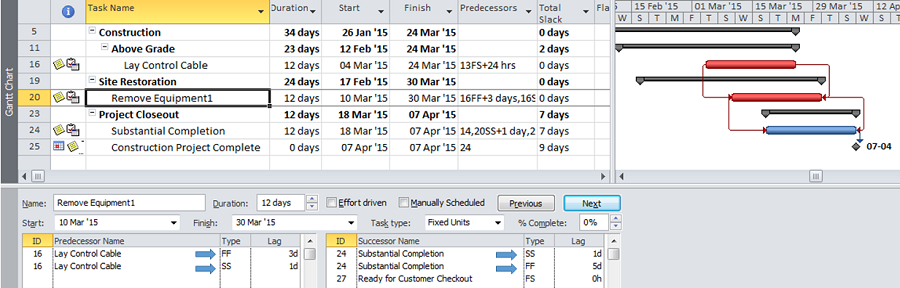

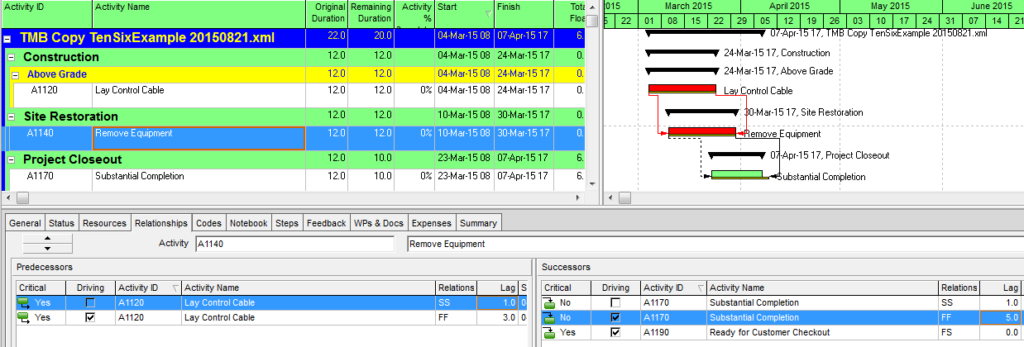

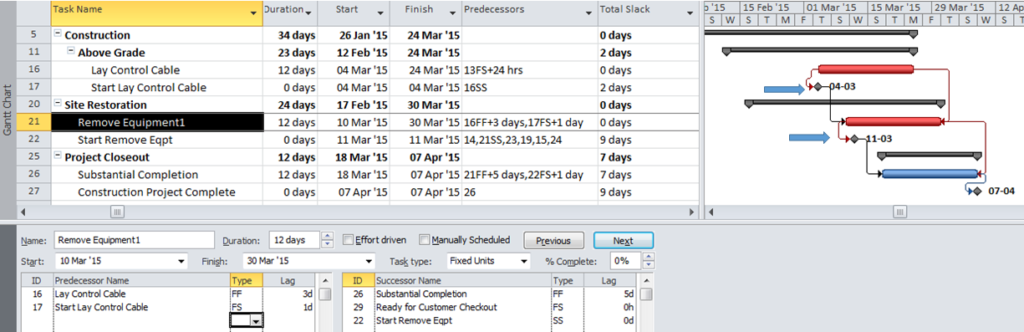

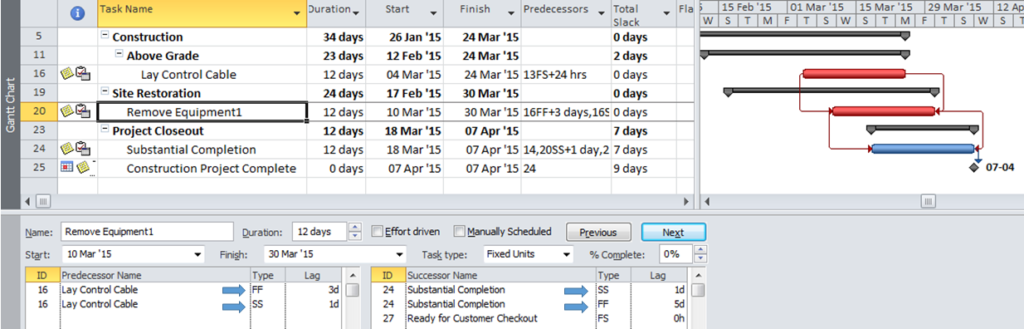

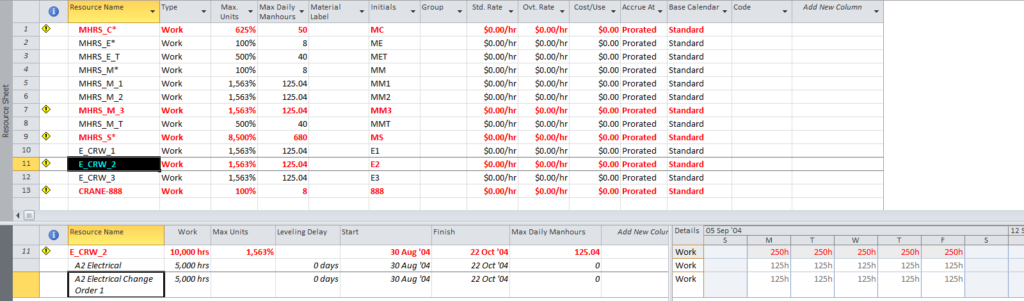

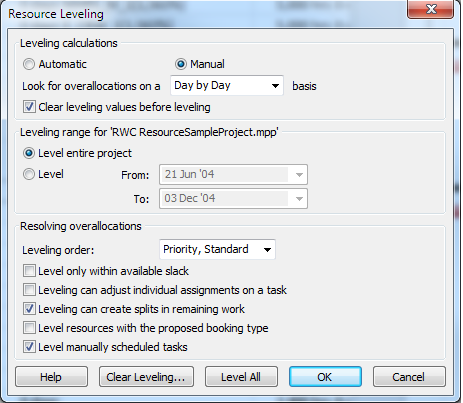

Modern CPM schedules often include deadlines or late constraints and multiple activity calendars, and they sometimes include resource leveling. All of these features can substantially affect the computation and interpretation of Total Float, such that it becomes an unreliable indicator of the Critical Path or of any logical path through the schedule. Thus complicated, it is still not useful for risk mitigation.

Finally, because of the float-sharing language that seems common in modern American construction contracts, it is useful to distinguish legitimate schedule buffers (e.g. contingency or TRA) from the vaguely-defined “project float.” That is, where “project float” exists primarily for risk mitigation, one should consider explicitly identifying and scheduling it as a “schedule contingency” (or “reserve” or “buffer”) activity extending from the early project finish to the contractual project finish.

Here is a link to an interesting article from Trauner Consulting on the subject of Shared Float provisions.

http://www.traunerconsulting.com/wp-content/uploads/Manginelli-Shared-Float-Article-FINAL-docx.pdf