The “critical” activity flags in modern project schedules often do not correctly identify the true critical paths. Blind acceptance of such “critical” flags to identify the critical path inhibits proper understanding, communication, and management of project schedule performance – and gives CPM a bad rap.

Basic CPM Concepts (in General):

The “critical path method” (CPM) – a ~60-year-old algorithm of fairly straightforward arithmetic – lies at the core of most modern project scheduling tools, and most project managers worthy of the name have been exposed to at least the basic CPM concepts. Any discussion of the critical path must address the underlying conceptual basis:

- A CPM project schedule is comprised of all the activities necessary to complete the project’s scope of work.

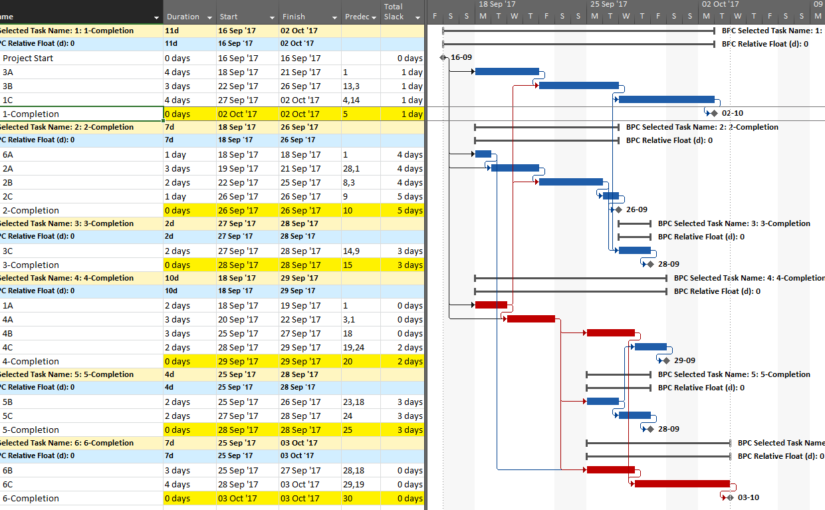

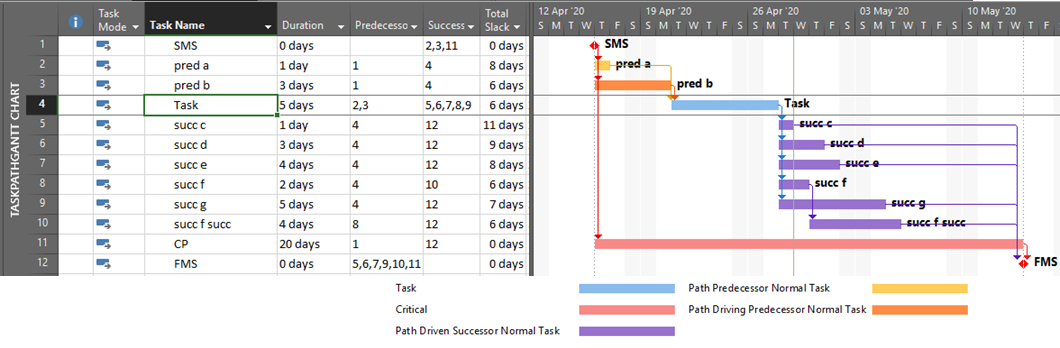

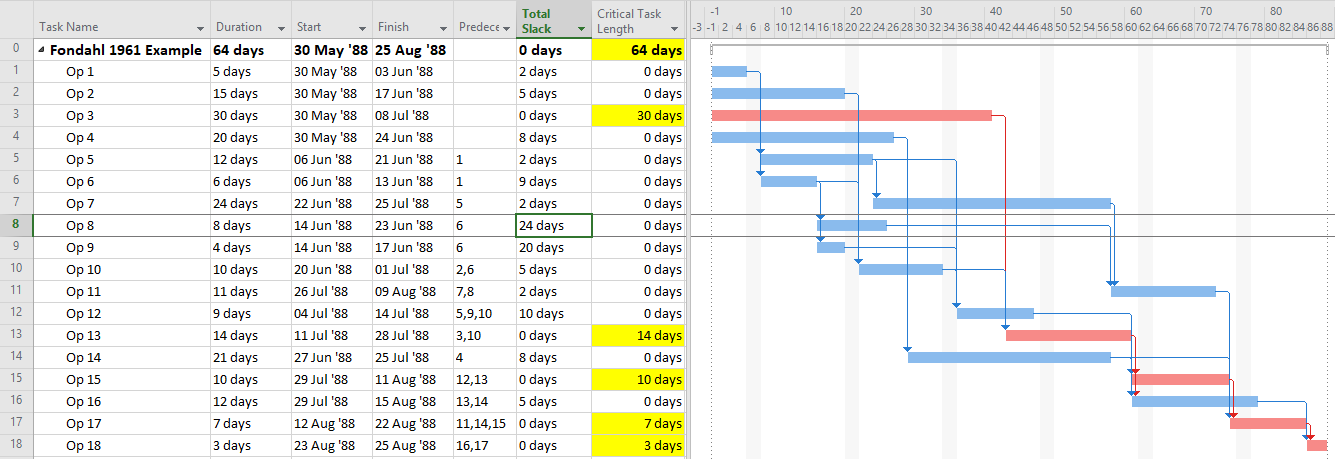

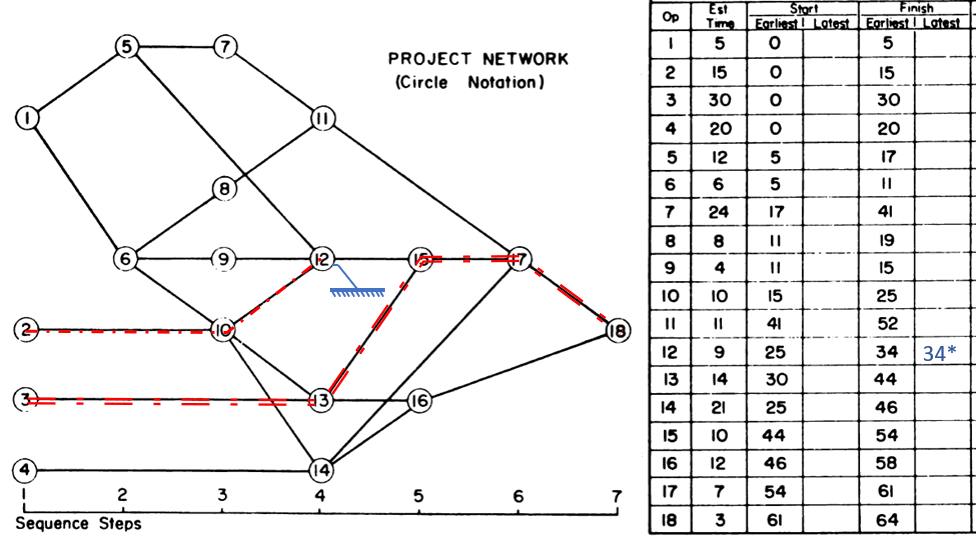

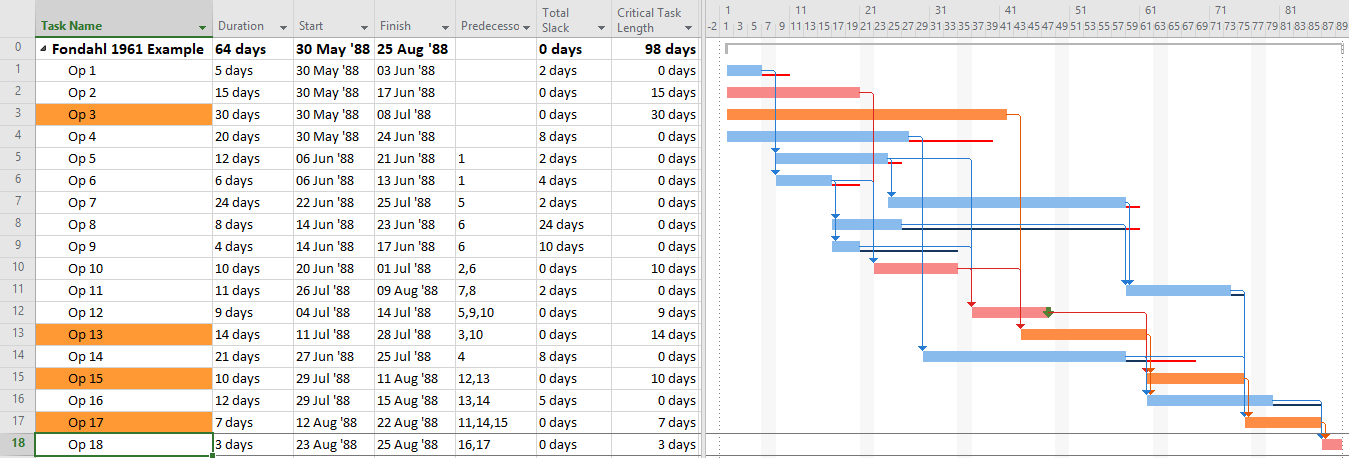

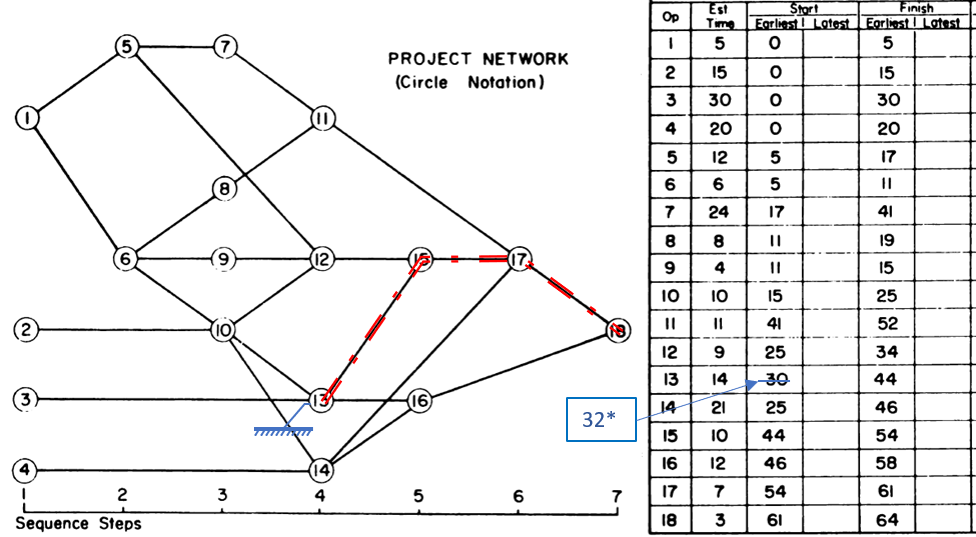

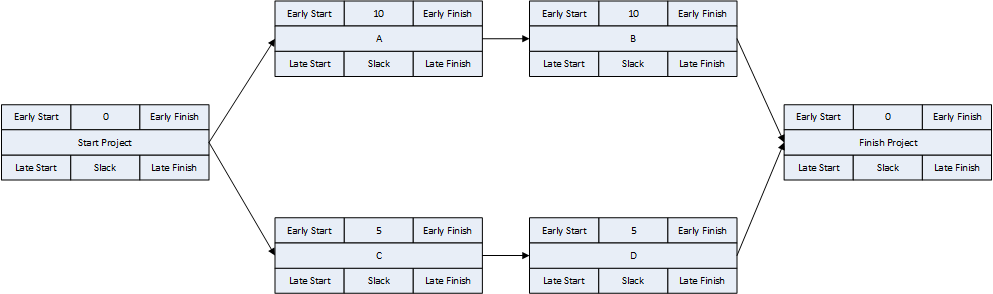

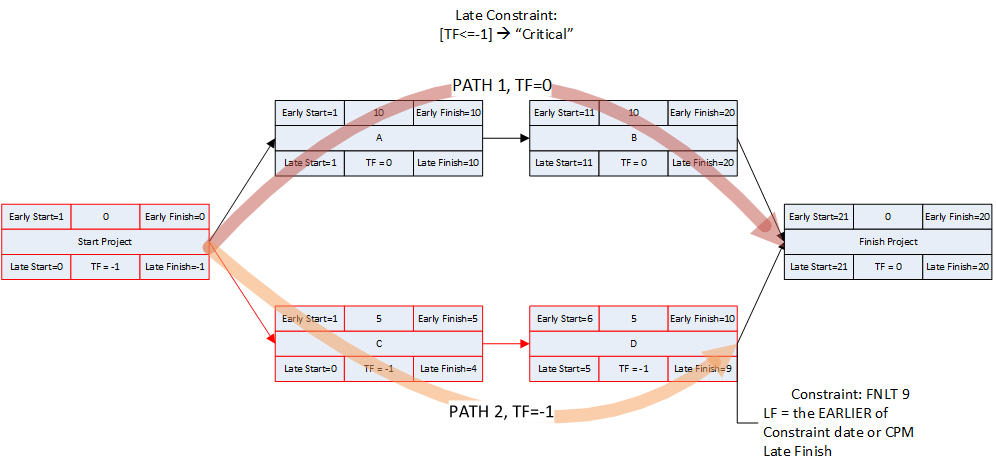

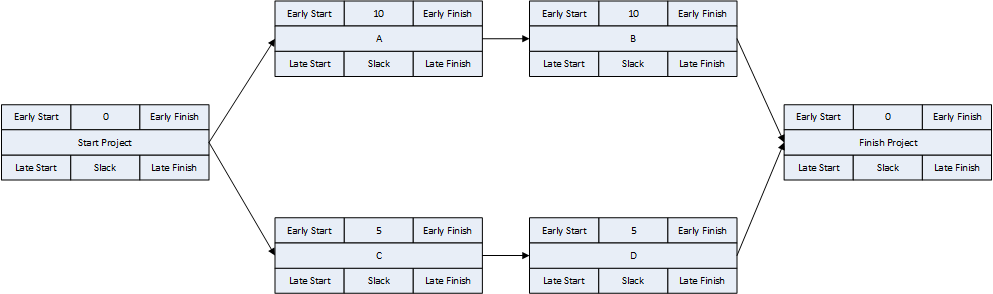

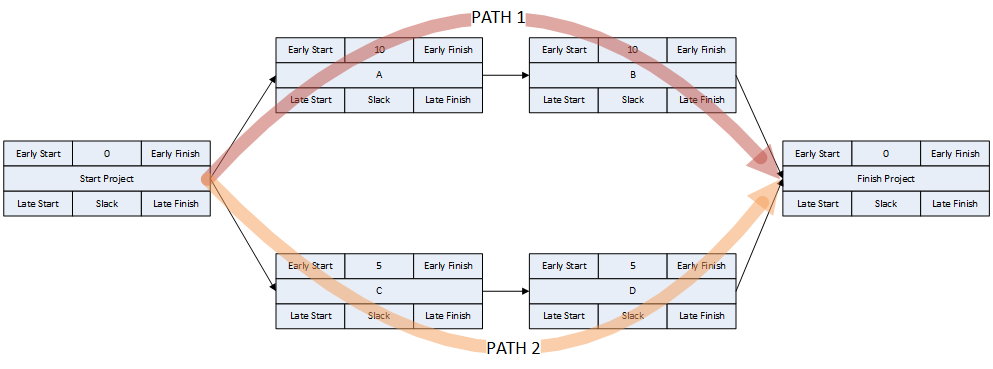

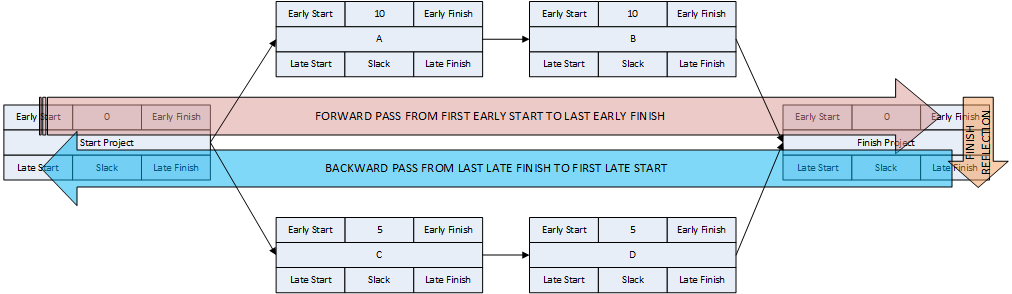

- Activity durations are estimated, and required/planned sequential restraints between activities are identified: e.g. Predecessor task “A” must finish before successor task “B” can start, and predecessor task “C” must finish before successor task “D” can start. The combination of activities and relationships forms a schedule logic network. Below is a diagram of a simple schedule logic network, with activities as nodes (blocks) and relationships as arrows.

- Logic Relationships. A logic relationship represents a simple (i.e. one-sided) schedule constraint that is imposed on the successor by the predecessor. Thus, a finish-to-start (FS) relationship between activities A and B dictates only that the start of activity B may NOT occur before the finish of activity A. (It does not REQUIRE that B start immediately after A finishes.) Other relationship types – SS, FF, SF, which were added as part of the precedence diagramming method (PDM) extension of traditional CPM – are similarly interpreted. E.g. A–>(SS)–>B dictates only that the start of B may not occur before the start of A. Activities with multiple predecessor relationships must be scheduled to satisfy ALL of them.

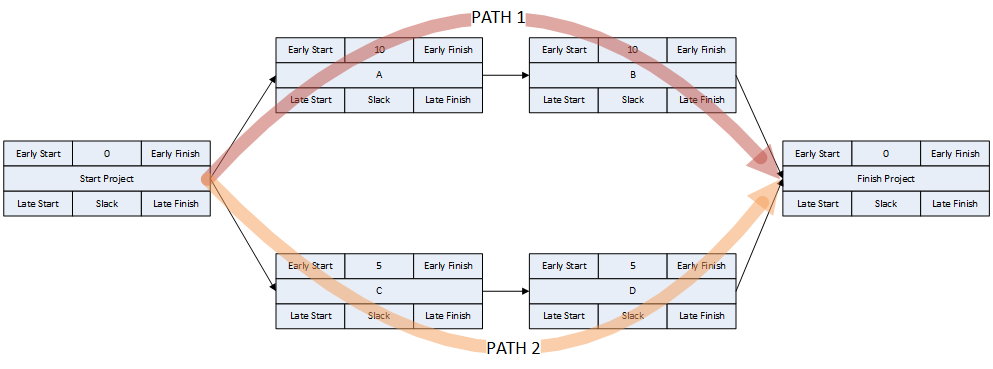

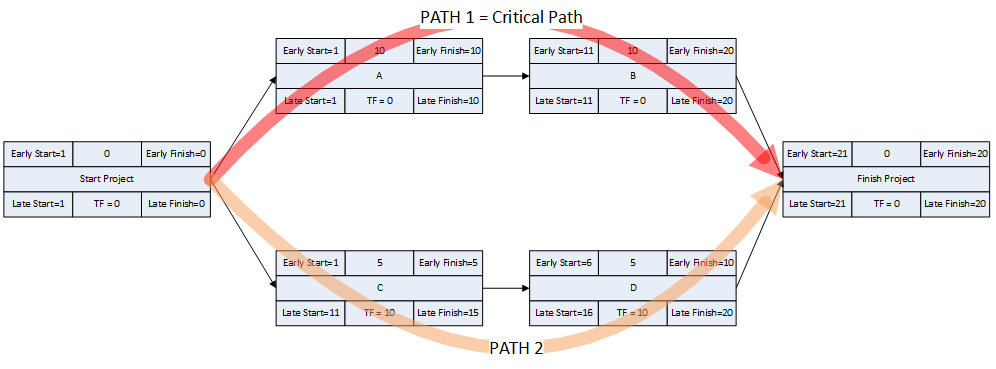

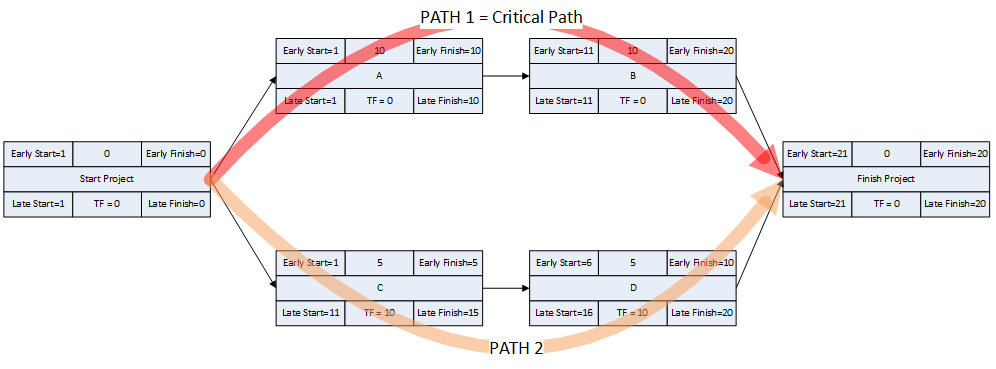

- Logic Paths. A continuous route through the activities and relationships of the network – connecting an earlier activity to a later one – is called a “logic path.” Logic paths can be displayed – together or in isolation – to show the sequential plans for executing selected portions of the project. The simple network shown has only two logic paths between the start and finish milestones: Path 1 = (StartProject) <<A><B>> (FinishProject); and Path 2 = (StartProject) <<C><D>> (FinishProject). [Experimenting with some shorthand logic notation: “<” = logic connection to activity’s Start; “>” = logic connection to activity’s Finish.]

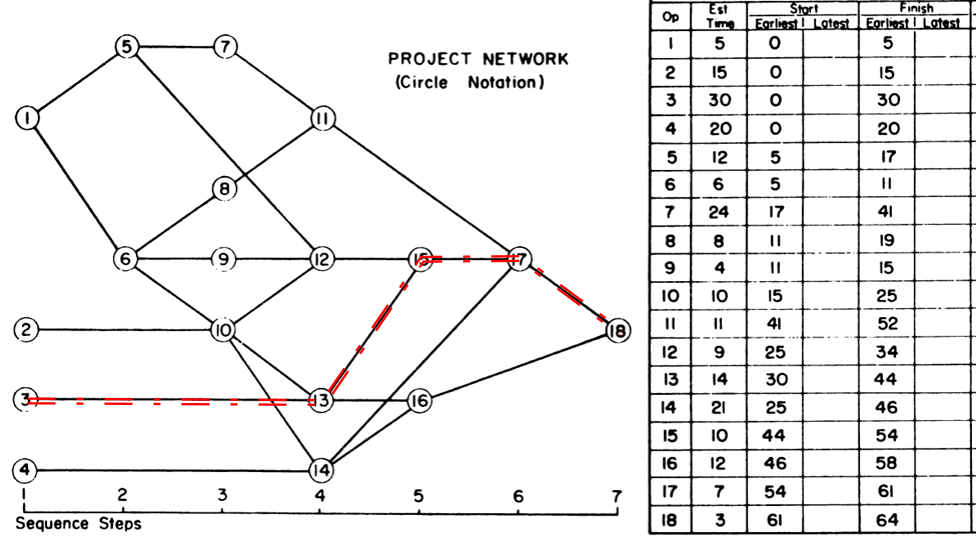

- Schedule Calculations. Schedule dates are calculated using three essential steps:

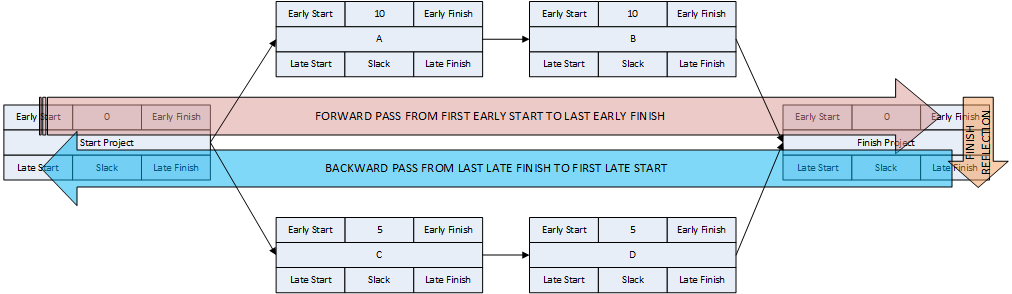

- During the forward pass, the earliest possible start and finish dates of each activity are computed by considering the aggregated durations of its predecessor paths, beginning from the project start milestone and working forward in time.

- Assuming an implicit requirement to finish the project as soon as possible, the early finish of the project completion milestone is adopted as its latest allowable finish date. This can be called the finish reflection. (Most CPM summaries ignore this step. I include it because it is the basis for important concepts and complications to be introduced later.)

- During the backward pass, the latest allowable start and finish dates of each activity are computed by considering the aggregated durations of its successor paths, beginning from the project completion milestone and working backward in time.

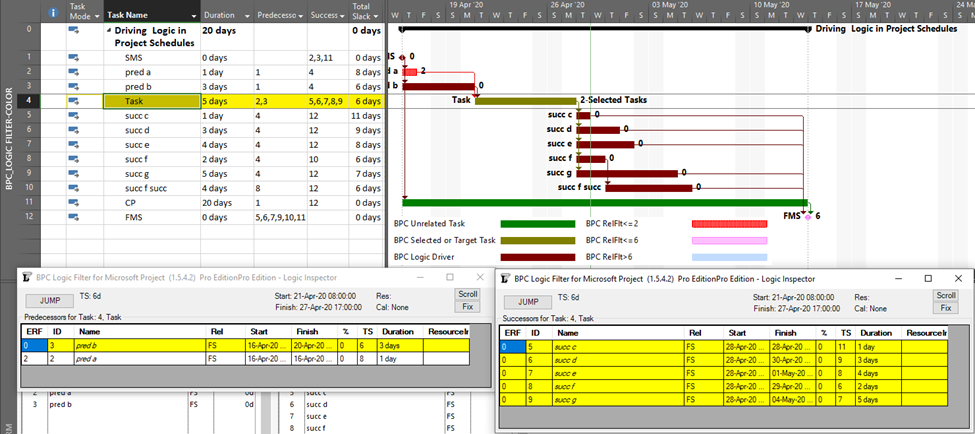

- Driving and Non-Driving Logic. A logic relationship may be categorized as “driving” or “non-driving” depending on its influence over the early dates of the successor activity – as calculated during the forward pass. A driving relationship controls the early start/finish of the successor; a non-driving relationship does not. In other words, a “driving” relationship prevents the successor activity from being scheduled any sooner than it is. A logic path (or path segment) may be categorized as “driving” (to its terminal activity) when all of its relationships are driving. [Such a path is sometimes called a “string.”]

- Total Float. In simplified terms, the difference between the early start/finish and late start/finish of each activity is termed the activity’s “total float” (or “total slack”). A positive value denotes a finite range of time over which the activity may be allowed to slip without delaying “the project.” A zero value (i.e. TF=0) indicates that the activity’s early dates and late dates are exactly equal, and any delay from the early dates may delay “the project.” It is important to remember that total float/slack is nominally computed as a property of each individual activity, not of a particular logic path nor of the project schedule as a whole. [While computed individually for each activity, the float is not possessed solely by that activity and is in fact shared among all the activities within a driving logic path. In the absence of certain complicating factors, it is common to refer to a shared float value as a property of that path.]

- Critical Path. A project’s critical path is the path (i.e. the unique sequence of logically-connected activities and relationships) that determines the earliest possible completion of “the project.” I prefer to call this the “driving path to project completion.” Other logic paths through the schedule are considered “near-critical paths” if they are at risk of becoming the critical path – possibly extending the project – at some time during project execution. In our simple project shown below, the critical path is Path 1, whose total duration of 4 weeks (20 days on a standard 5dx8h calendar) controls the early finish of the completion milestone.

In unconstrained schedule models incorporating only a single calendar (and without other complicating factors), the finish reflection causes the activities on the critical path to have late dates equal to their early dates; i.e. TF = 0. Consequently, any delay of a critical-path activity cascades directly to delay of the project completion. The near-critical paths are then defined as those paths whose activities have TF more than zero but less than some threshold. In traditional “critical path management,” activities that are NOT on or near the critical path may be allowed to slip, while management attention and resources are devoted to protecting those activities that are on or near the critical path. More importantly, acceleration of the project completion (or recovery from a prior delay) may only be accomplished by first addressing the activities and relationships on the critical path.

[Note: The definition of “critical path” has evolved with the introduction of new concepts and scheduling methods over the years. The earliest definitions – based on robust schedule networks containing only finish-to-start relationships, with no constraints, no lags, and no calendars – were characterized by the following common elements:

- It contained those activities that determined the overall duration of the project (i.e. the “driving path to project completion.”)

- It contained those activities that, if allowed to slip, would extend the duration of the project (hence the word “critical”).

- A delay of any of its activities would be directly transmitted to an equal (matching) delay of the project completion.

- Its activities comprised the “longest path” through the schedule network. That is, the arithmetic sum of their durations was greater than the corresponding sum for any other path in the network.

- After completion of the forward and backward passes, its activities could be readily identified by a shared total float value of zero. Thus TF=0 became the primary criterion for identifying the critical path.

With the incorporation of non-FS relationships, early and late constraints, lags, and calendars in modern project scheduling software, these observations are no longer consistent with each other nor sometimes with a single logic path. Some of these inconsistencies are addressed later in this article. Only the first of these defining elements (“driving path to project completion”) has been generally retained in recent scheduling standards and guidance publications, though implied equivalence of the others continues to persist among some professionals.]

Software – the Critical Activities / Critical Tasks:

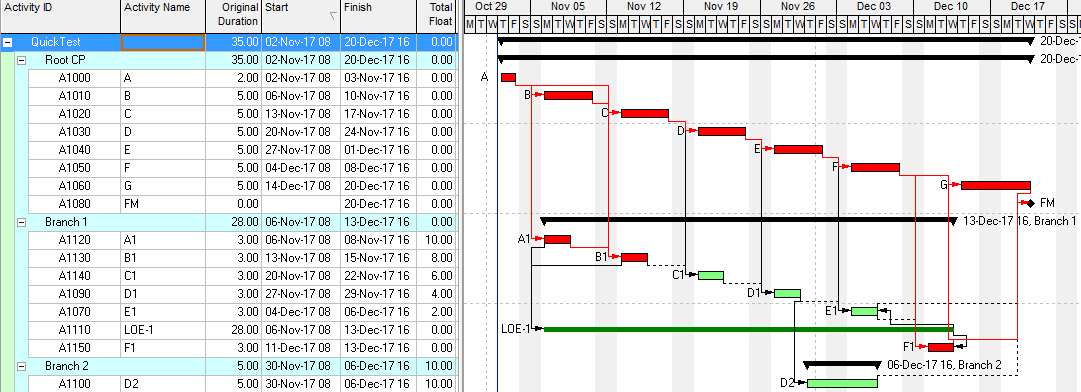

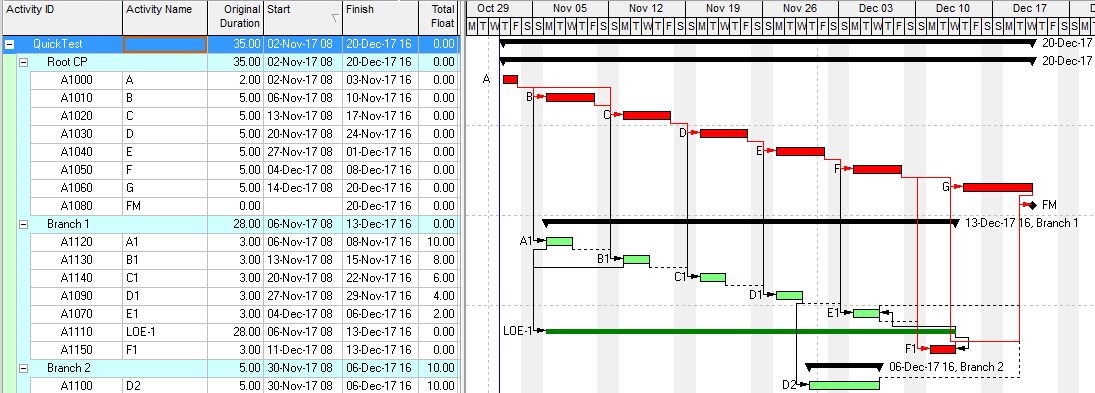

The basic element of modern project schedules is the activity or task. In most scheduling tools, logic paths are not explicitly defined. Nevertheless, the obvious importance of the critical path dictates that software packages attempt to identify it – indirectly– by marking activities that meet certain criteria with the “critical” flag. Activities with the “critical” flag are called “critical activities” (or “critical tasks”) and are typically highlighted red in network and bar-chart graphics.

Applying Critical Flags using Default Total Float Criteria

The simplest criterion for flagging a task as “critical” is TF=0. This is the primary method that most new schedulers seem familiar with, and it is the default criterion for some software packages. As noted earlier, this criterion is applicable to schedules with no constraints and only a single calendar. In Microsoft Project (MSP) and Oracle Primavera P6 (P6), the default “critical” flag criterion is TF<=0, and the threshold value of “0” can be adjusted. The differences between these criteria and the simpler TF=0 criterion are justified by four primary concerns:

- Risk Management. Due to the inherent uncertainty of activity duration estimates, the critical path of a real-world project schedule – as ultimately executed – often includes an unpredictable mix of activities from the as-scheduled critical path and near-critical paths. In the absence of quantitative schedule risk assessment, it is reasonable to consider all such (potentially-critical-path) activities equally when evaluating project schedule risks. This purpose is easily served by applying the “critical” flag to all activities whose TF value is less than or equal to some near-critical threshold.

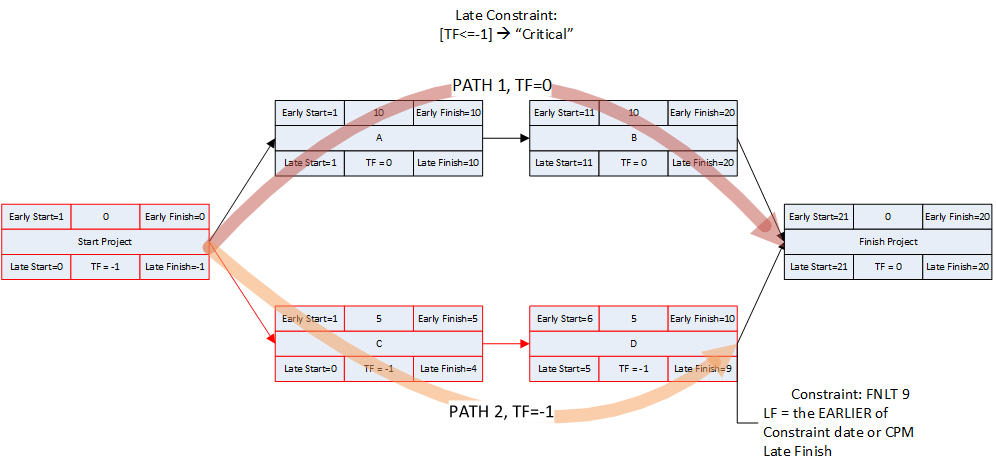

- Late Constraints. Overall project completion priorities (and contractual requirements) often lead to the imposition of deadlines (in MSP), late-finish constraints (in MSP and P6), or project constraints (in P6). Such constraints can override the finish reflection and cause the late dates of some activities to be earlier or later than they would be in the absence of the constraints. As a result, total float can vary among the activities on the driving path to project completion. In a project with multiple constrained milestones, the driving path to only one of them (the most “urgent”) can be expected to have a constant total float value (i.e. the lowest total float.) Due to intersecting logic paths, total float can vary along the driving paths to other constrained milestones. Applying the “critical” flag to activities with total float less than or equal to the project’s lowest total float marks those activities that are on the driving path to the most urgent constrained milestone in the project. If a project constraint (in P6 only) is applied, the lowest total float value may be greater than zero; without a more urgent constraint, the marked activities then denote the driving path to the final activity in the project.

- Negative Float. Late constraints can cause late dates to precede early dates for certain activities. This results in negative values for total float/slack (i.e. TF<0). In practically all cases, negative total float indicates that the activity cannot be scheduled in time to satisfy one or more of the deadlines or constraints (though which one of these is violated may not be clear); and some corrective action is necessary. [*The concept of negative float – and the constraints that create it – were not included in the foundations of CPM and PDM. Negative float is not universally accepted among scheduling professionals today, and not all scheduling software supports its calculation.]

Applying the “critical” flag to all activities with total float less than or equal to zero then marks all activities that:

-

- Are on the driving path to an unconstrained project completion (i.e. TF=0, controlled by the project’s finish reflection); or

- Are on the driving path to a constrained project completion or intermediate milestone that is just barely met (i.e. TF=0, controlled by deadline/constraint); or

- Are on the driving path to project completion where an explicit project completion milestone is violated (i.e. TF<0, controlled by project deadline/constraint); OR

- Are on the driving path to some intermediate activity whose constraint is violated (i.e. TF<0, controlled by intermediate deadline/constraint); or

- Are on any number of non/near-driving paths to one or more constrained project completion or intermediate milestones, (i.e. TF<0). Though non-driving, these paths must still be shortened (in addition to shortening the driving and nearer-driving paths) to meet the milestones.

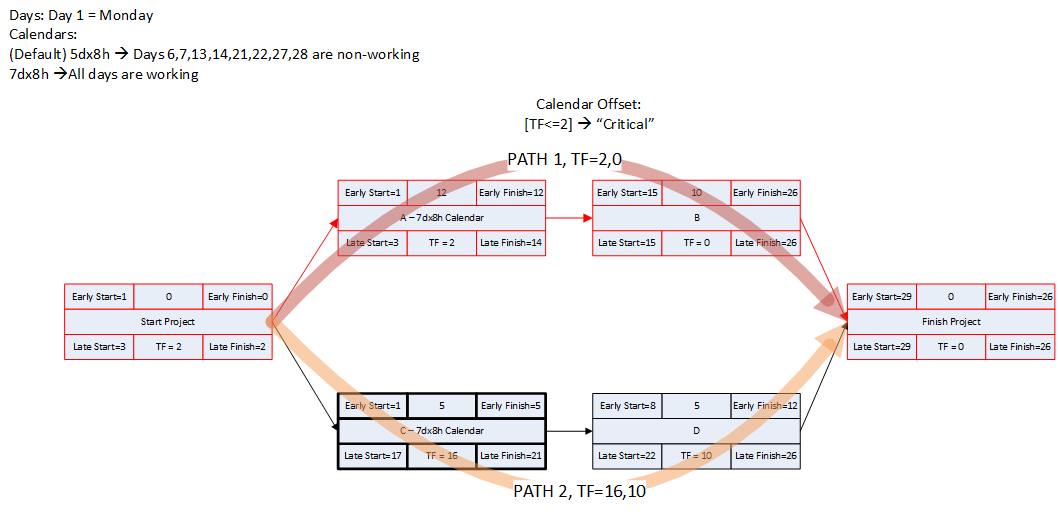

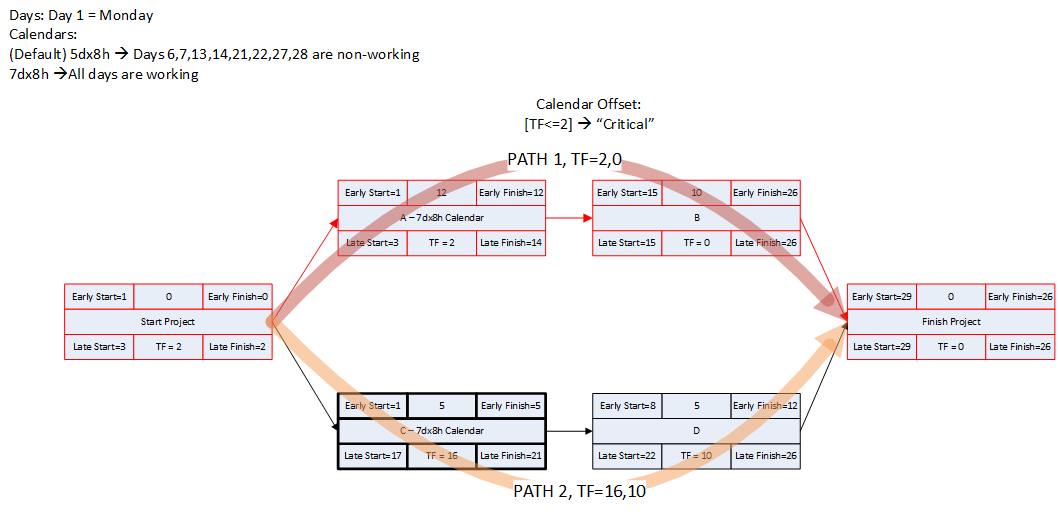

- Working-Time Calendar Effects. When activities with different calendars are logically connected in a schedule network, the interval between the finish of a predecessor task and the start of its successor may sometimes contain working time for the predecessor but not for the successor. If this occurs, then a driving logic relationship exists, but the predecessor still has room to slip without delaying any other tasks or the project (i.e. it possesses float.) More generally, when a driving logic path contains activities with different calendars, the interval between the early and late dates of one activity may contain more or less worktime than the corresponding intervals of its mates on the path. Thus, total float may vary along a single driving logic path, including the critical path. The amount of this variation depends on the size of potential offsets between calendars: from a few hours (for shift calendar offsets) to a few days (for 5-day and 7-day weekly calendars offsets) to a few months (for seasonal-shutdown calendar offsets).

Applying the “critical” flag to all activities with total float less than or equal to the largest calendar-related offset will mark all activities that:

- Are on the driving path to project completion with TF<=0;

- Are on the driving path to project completion but with TF>0 (and less than the specified offset);

- Are NOT on the driving path to project completion but have TF less than the specified offset. These are false positives. For these activities, total float could be controlled either by the finish reflection (TF>=0) or by some other constraint.

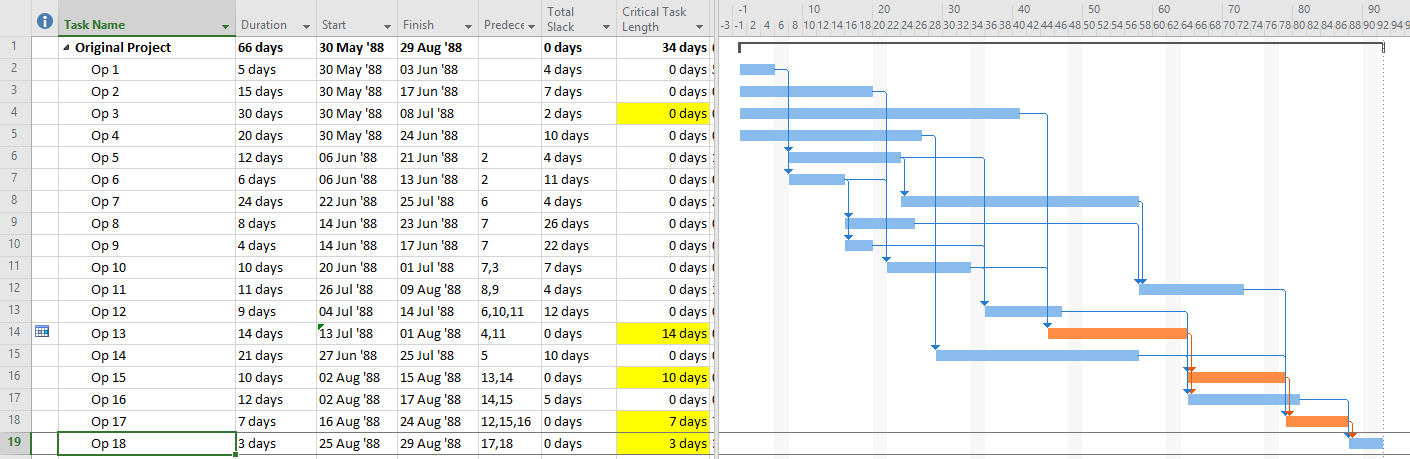

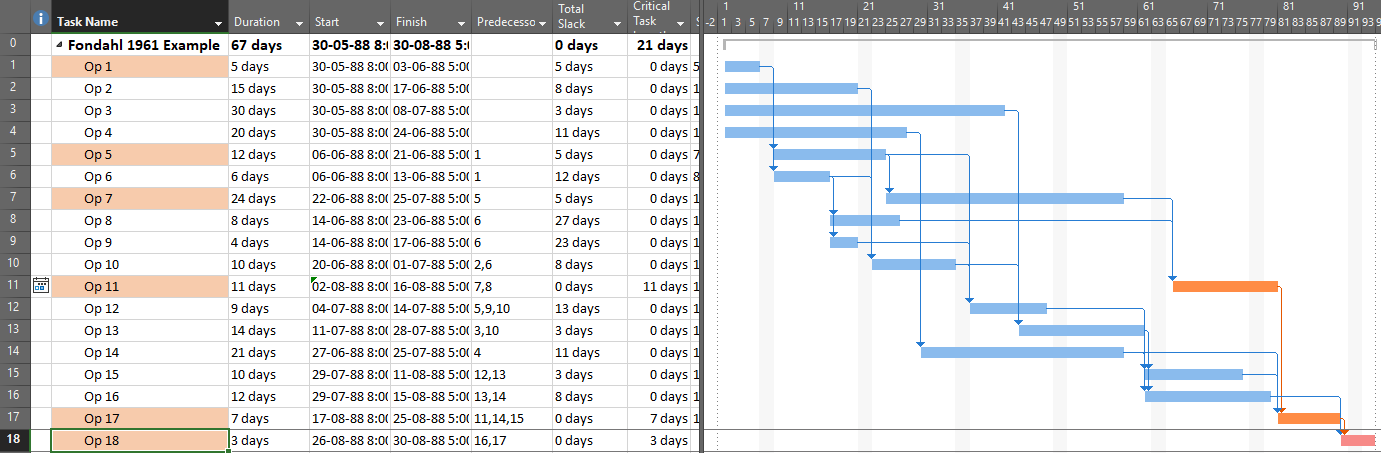

Critical Flags and Critical Paths

Unfortunately, applying the “critical” flag as noted for most of these considerations has one consistent result: the continuous sequence of activities and relationships constituting a “critical path” often remains obscured. It is disappointing that the majority of project schedulers – using MSP or P6 – continue to issue filtered lists of “critical” activities as “the critical path.” Much of the time – especially in MSP – they are not. Even among expert schedulers, there is a persistent habit of declaring total float as the sole attribute that defines the critical path rather than as a conditional indicator of an activity’s presence on that path.

When an activity is automatically marked “critical” based on total float/slack, the primary conclusion to be drawn is simply, “this activity has total float/slack that is at or below the threshold value. That is, there is insufficient working time available between the early- and late- start/finish dates.” If total float/slack is less than zero, then one might also conclude, “this activity is scheduled too late to meet one or more of the project’s deadlines/constraints.” [If automatic resource leveling has been applied, then even these simple conclusions are probably incorrect.] These are important facts, but a useful management response still requires knowledge of the driving logic path(s) to the specific activities/milestones whose deadlines/constraints are violated – knowledge that total float/slack and its associated “critical” flag do not always provide.

Workarounds for Total Float Criteria

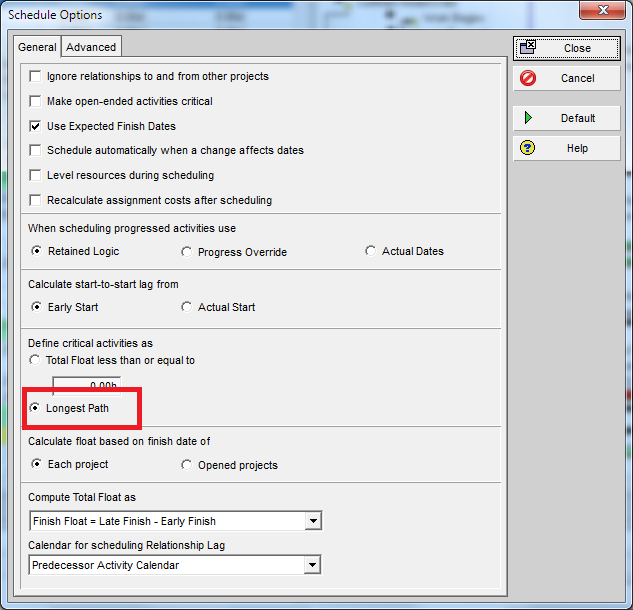

P6 provides several features, not available out-of-the-box in MSP, for correctly identifying the critical path when total float criteria do not. Specifically:

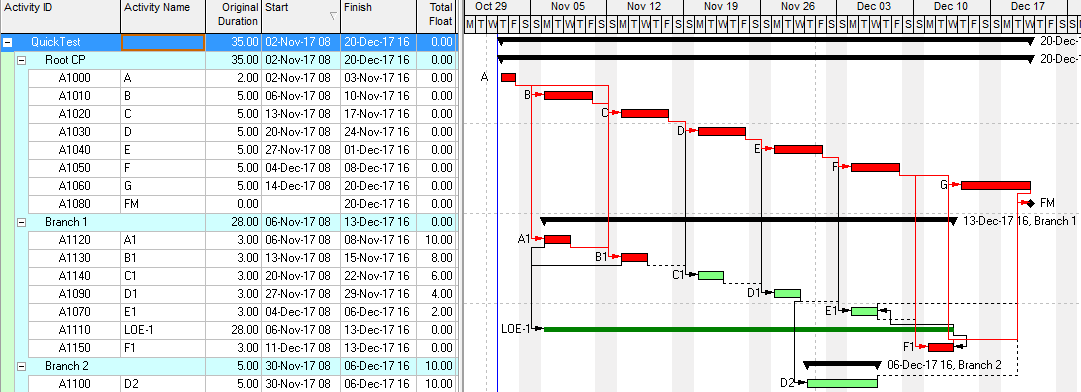

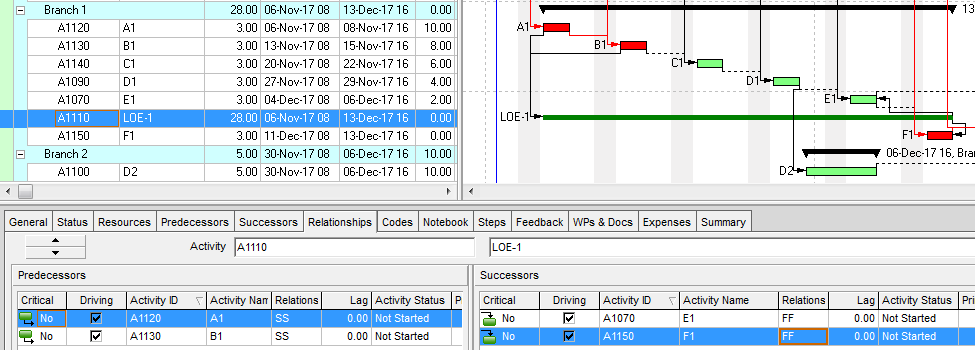

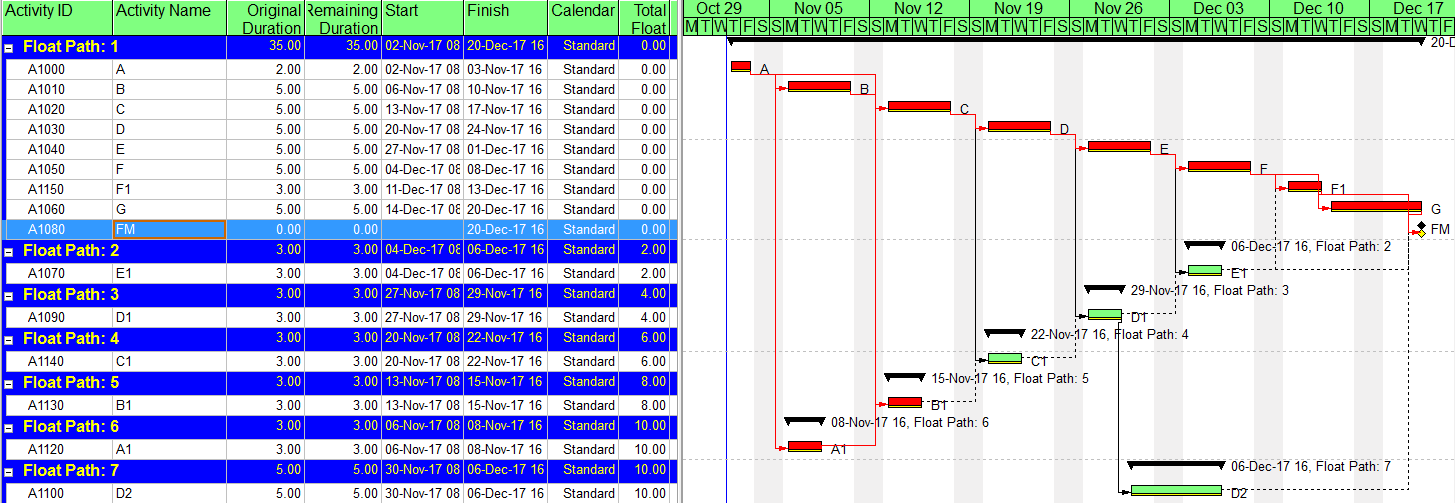

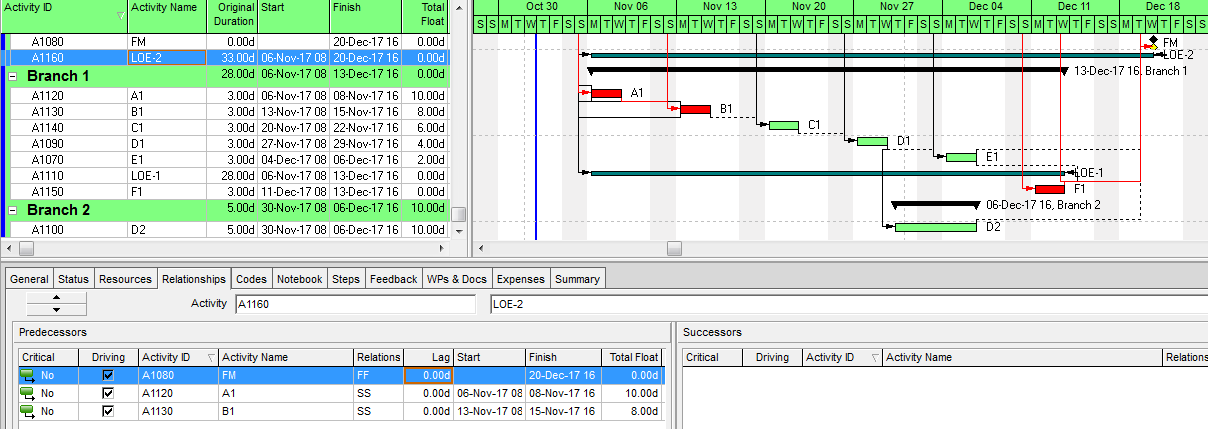

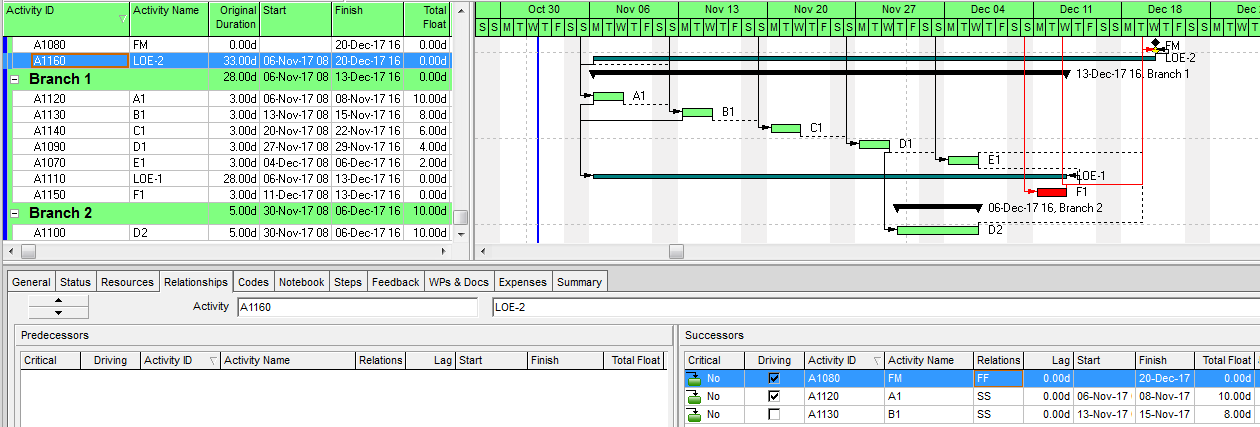

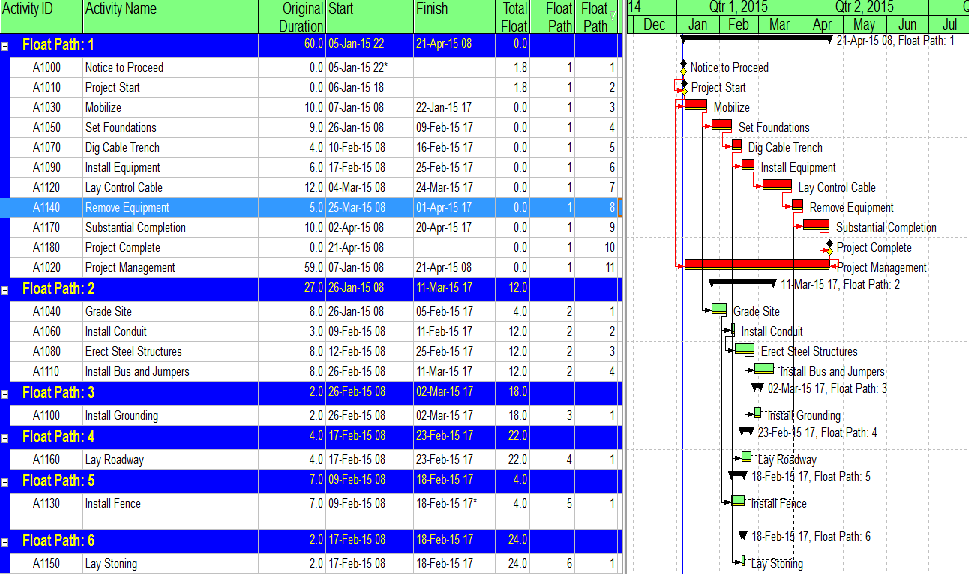

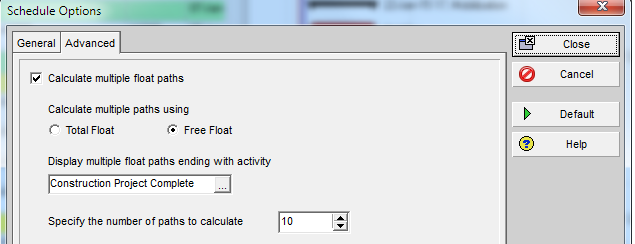

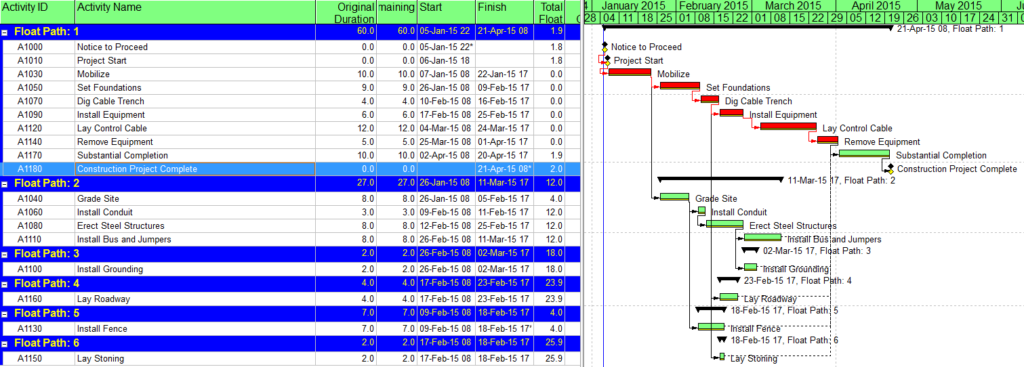

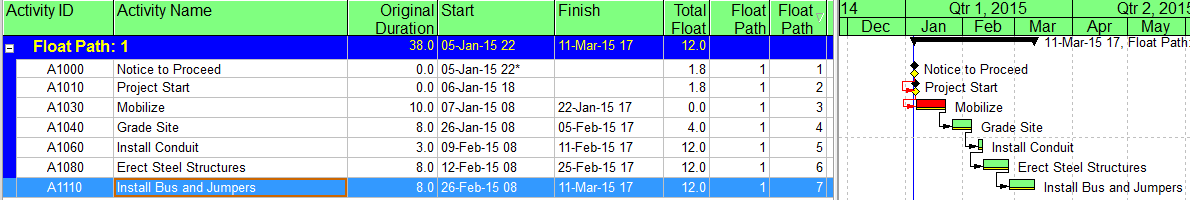

- For Risk Management. P6’s multiple-float path analysis (MFP) allows the identification of successive driving and near-driving paths to specified project completion milestones. Monitoring progress on these paths is worthwhile for risk management. I’ve previously written about MFP analysis HERE. P6 does not support using float paths (the output of MFP analysis) as an explicit criterion for the “critical” activity flag.

- For Late Constraints and Negative Float. P6 allows a negative critical float threshold. It is possible to set this threshold low enough so that only the path of lowest total float is marked as critical. In the absence of working time calendar effects, this criterion can be effective in identifying the (most) critical path. Thus it is possible to correctly identify the project’s critical path when: a) there is only a single constraint on the project; and b) that constraint coincides with the sole project completion milestone; and c) that constraint is violated (creating negative float).

- MSP does not allow a negative critical float threshold, so correct identification of the critical path in a negative float scenario is not possible. All tasks with negative total slack are automatically and unavoidably flagged as “critical.”

- If the P6 schedule has a project “must finish by” constraint, then the activities on the critical path may have positive total float. In that case, the lowest-float criterion may be applied (using a positive threshold) to correctly identify the critical path.

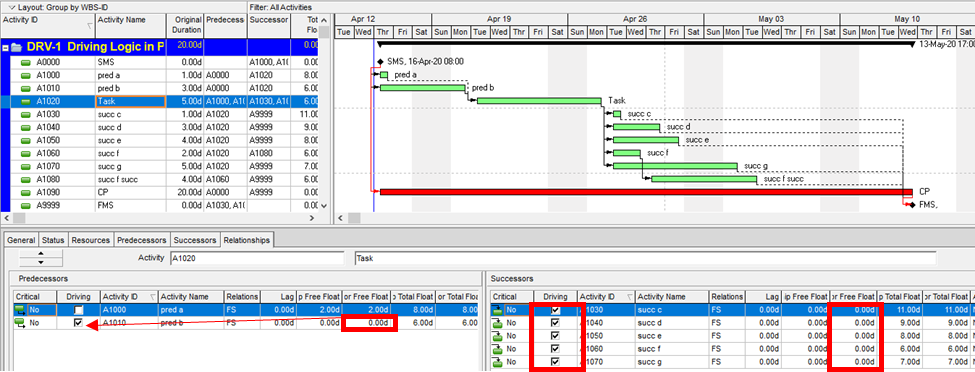

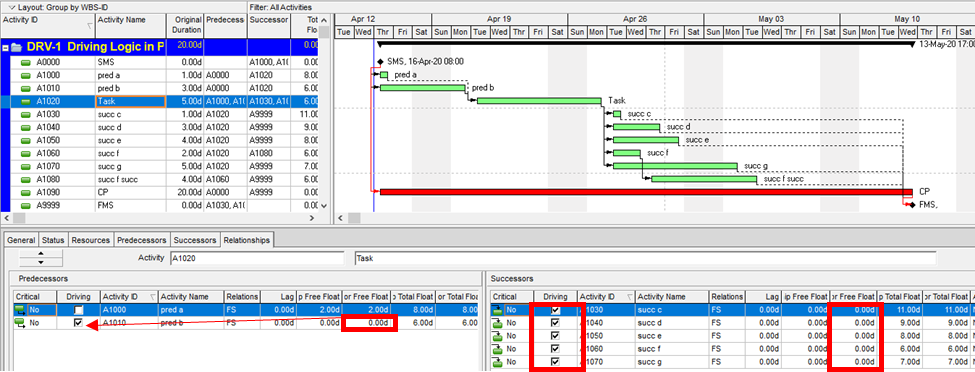

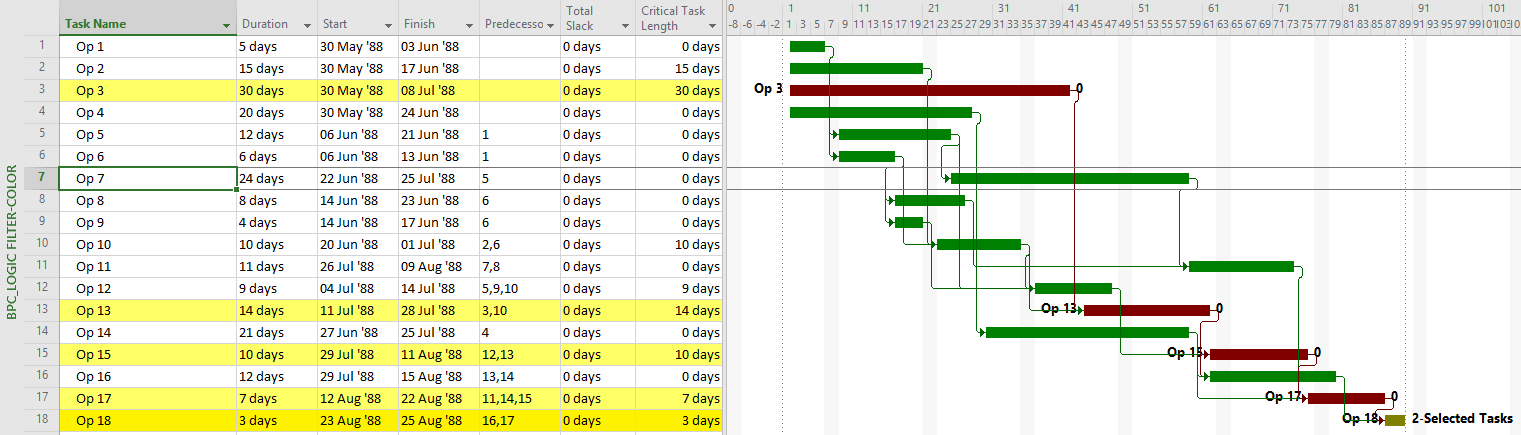

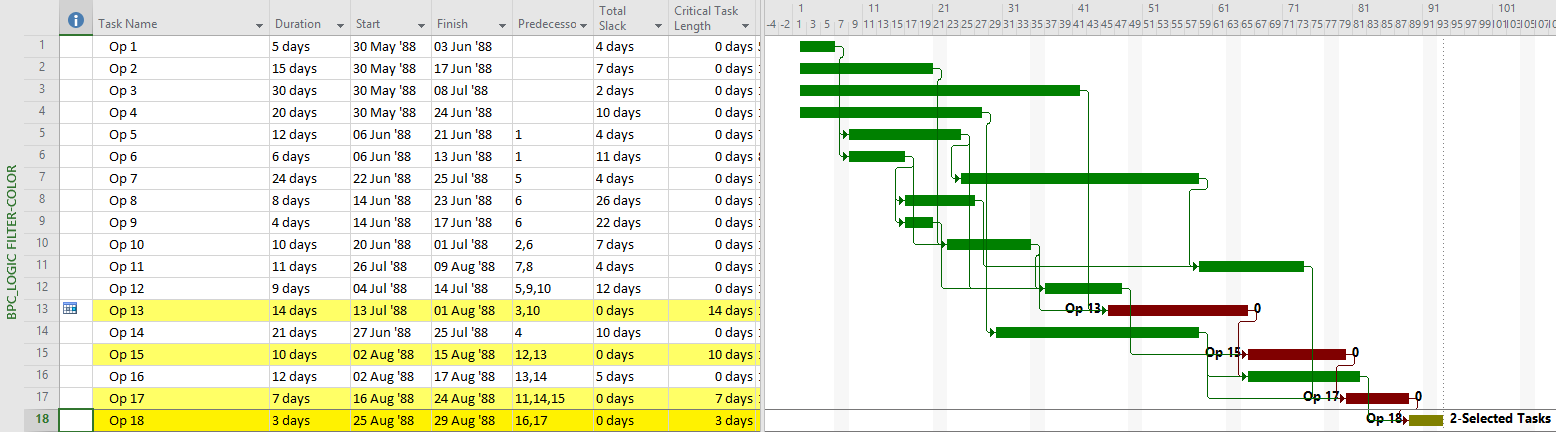

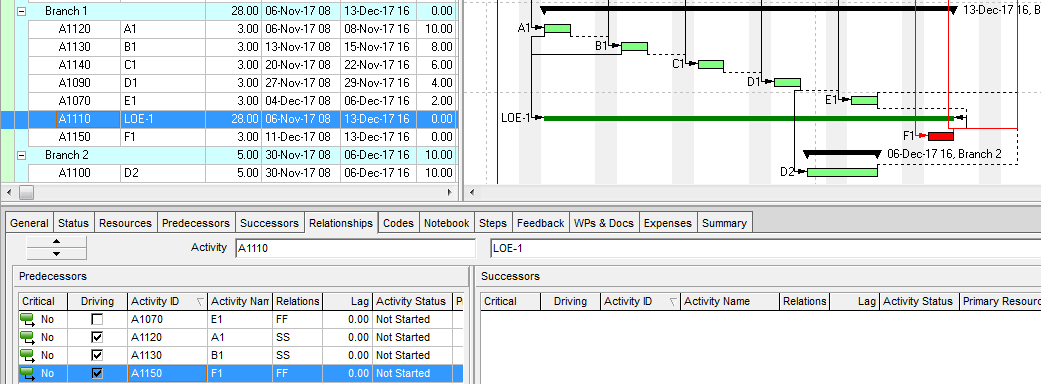

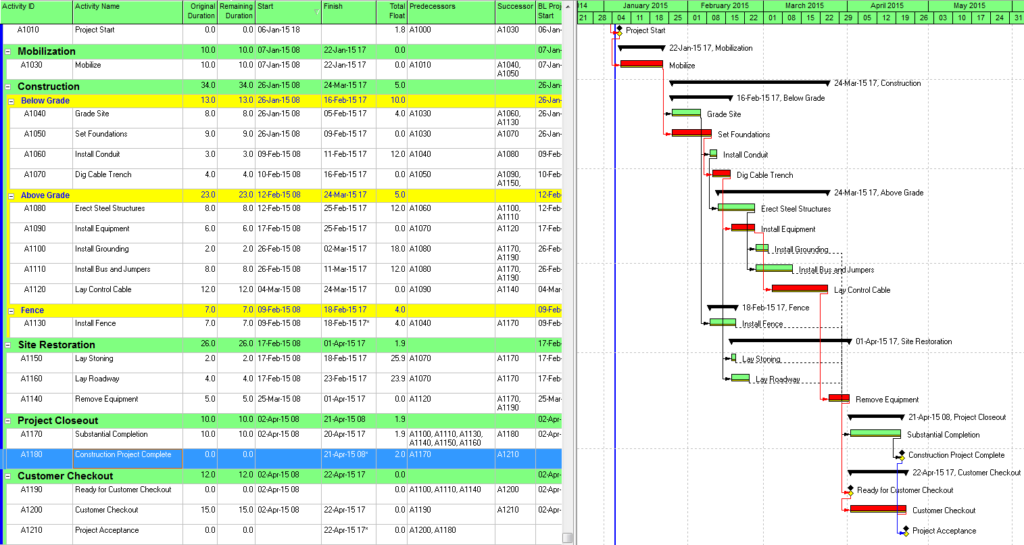

- For Working-Time Calendar Effects. Unlike other project scheduling software, P6 allows the “critical” activity flag to be assigned on the basis of some criterion other than total float – called Longest Path. The name is misleading, as the method is based on driving logic rather than activity durations. Any activity that is found on the driving logic path to project completion is flagged as “critical.” (The algorithm tracks driving logic backward from the task(s) with the latest early finish in the project.) The Longest Path criterion ignores the total float impacts of multiple calendars and constraints. While it is effective in identifying the project’s critical (logic) path, Longest Path alone is not useful for identifying near-critical paths. MFP analysis (noted above) is useful for this purpose. “Longest path value ™,” a relative-float metric available in Schedule Analyzer Software (a P6 add-in) also helps to identify near-critical paths in these circumstances. For a more detailed review, see What is the Longest Path in a Project Schedule?

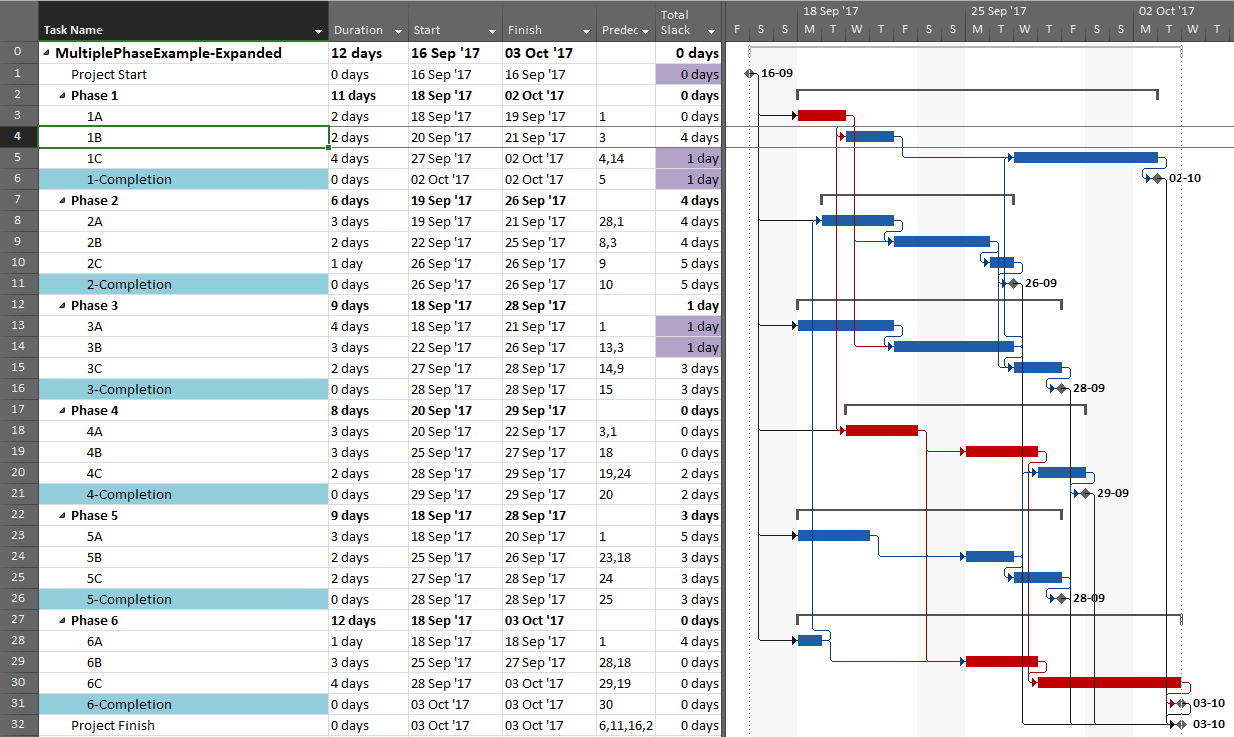

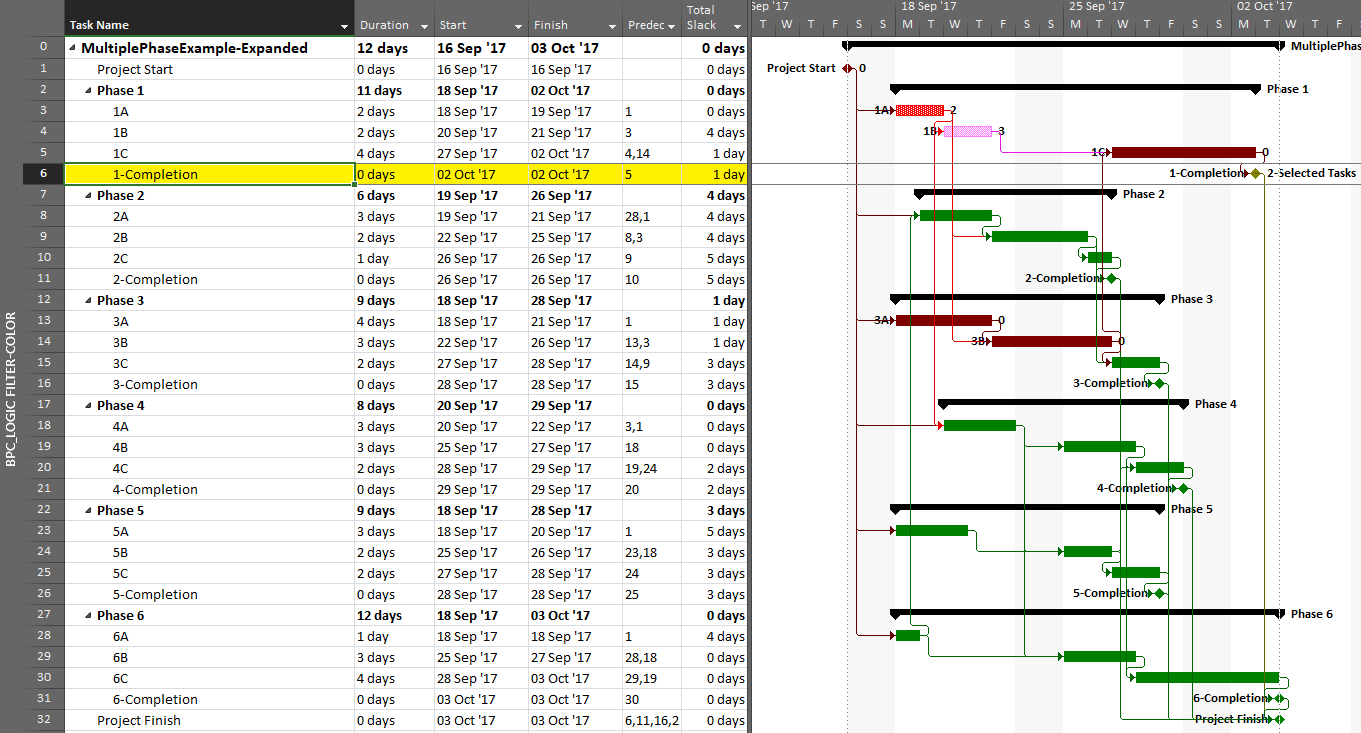

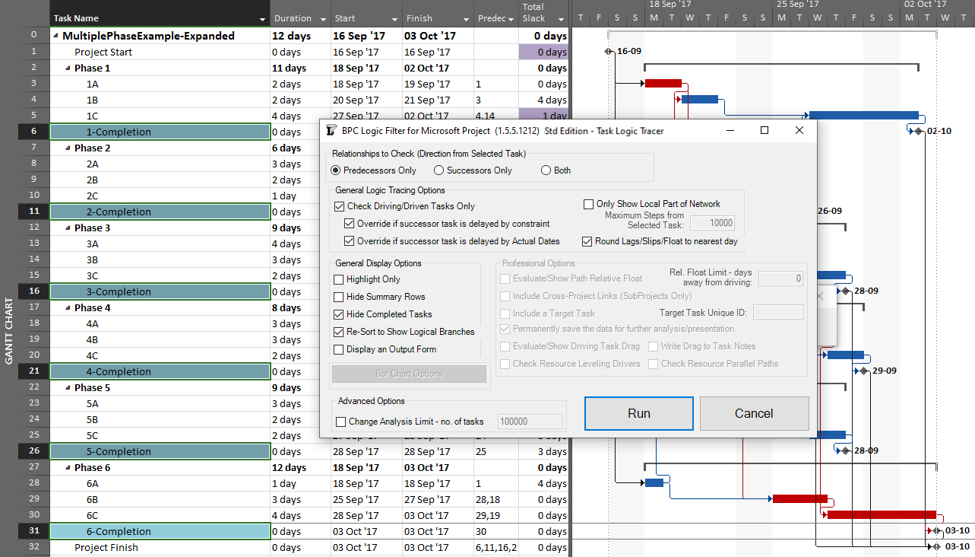

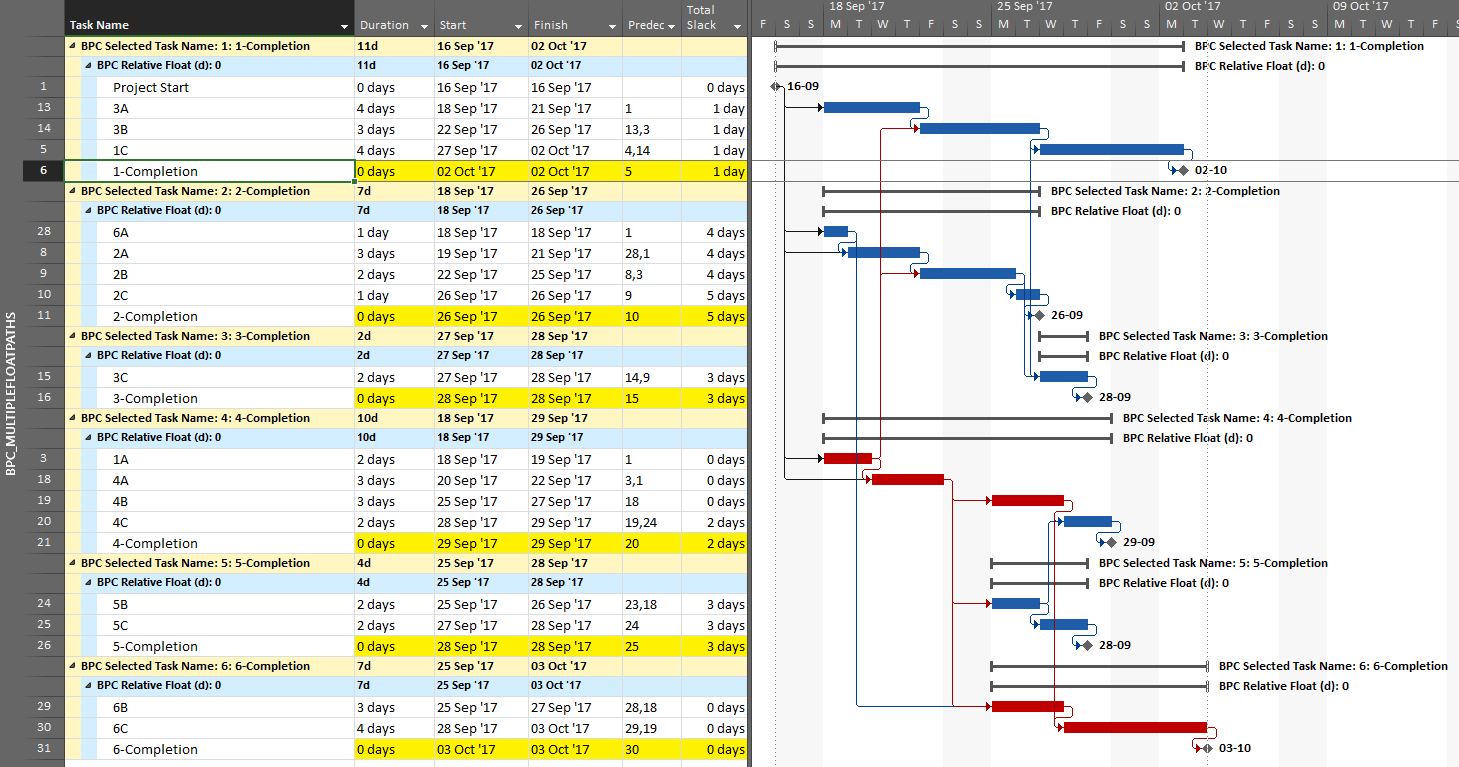

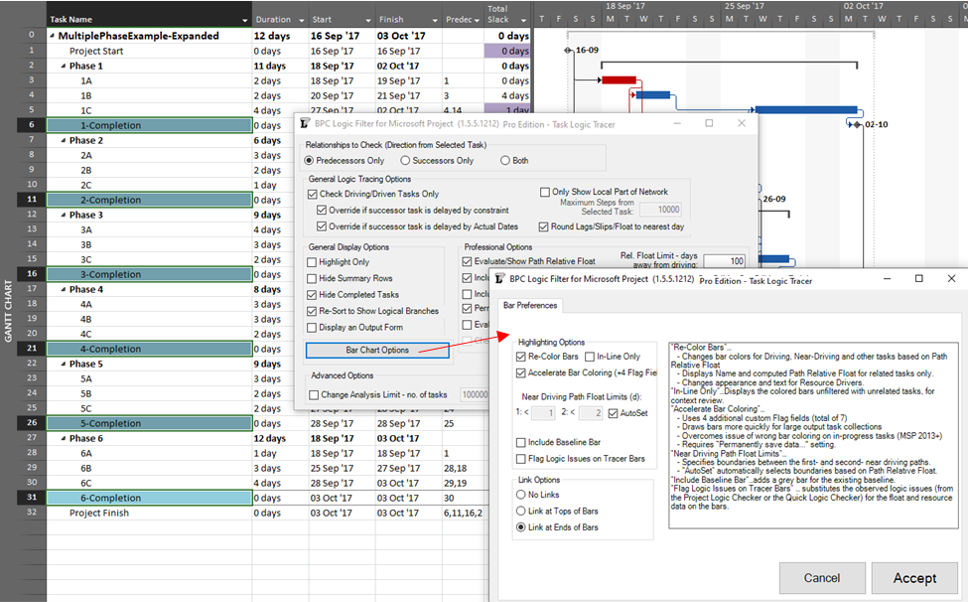

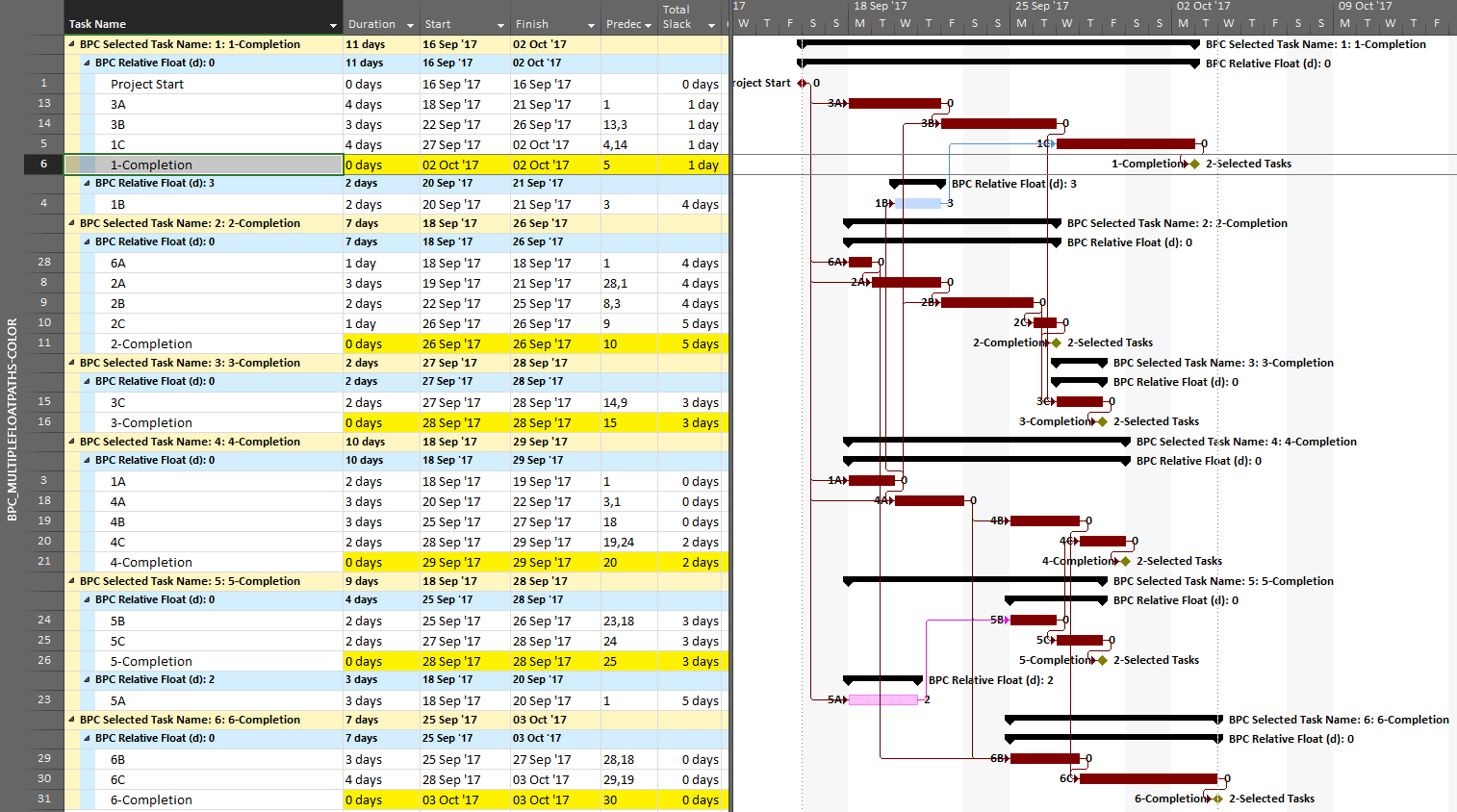

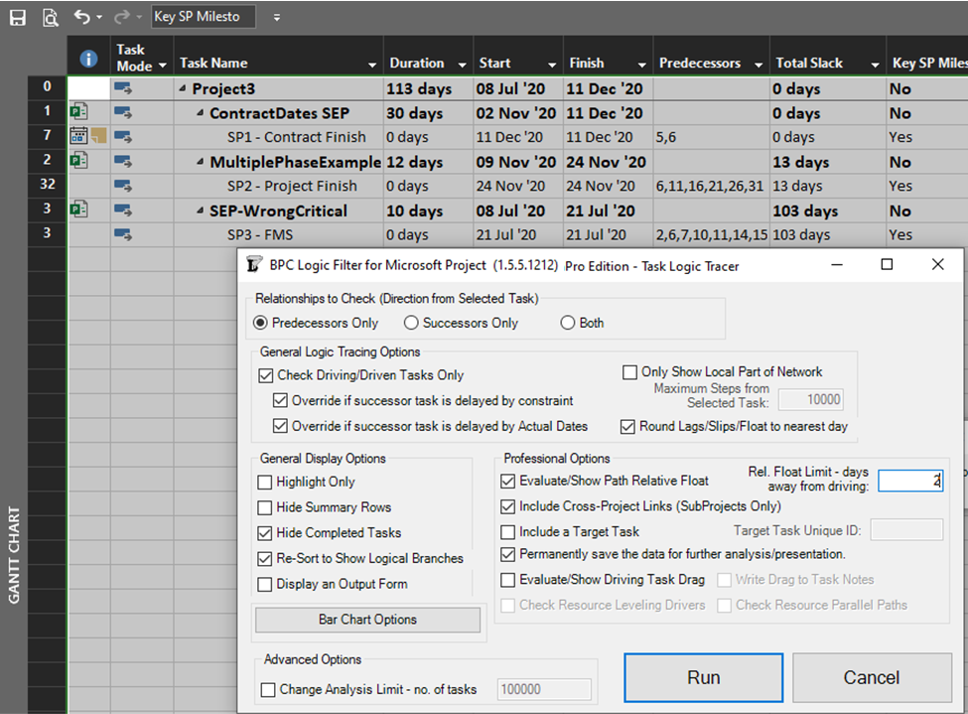

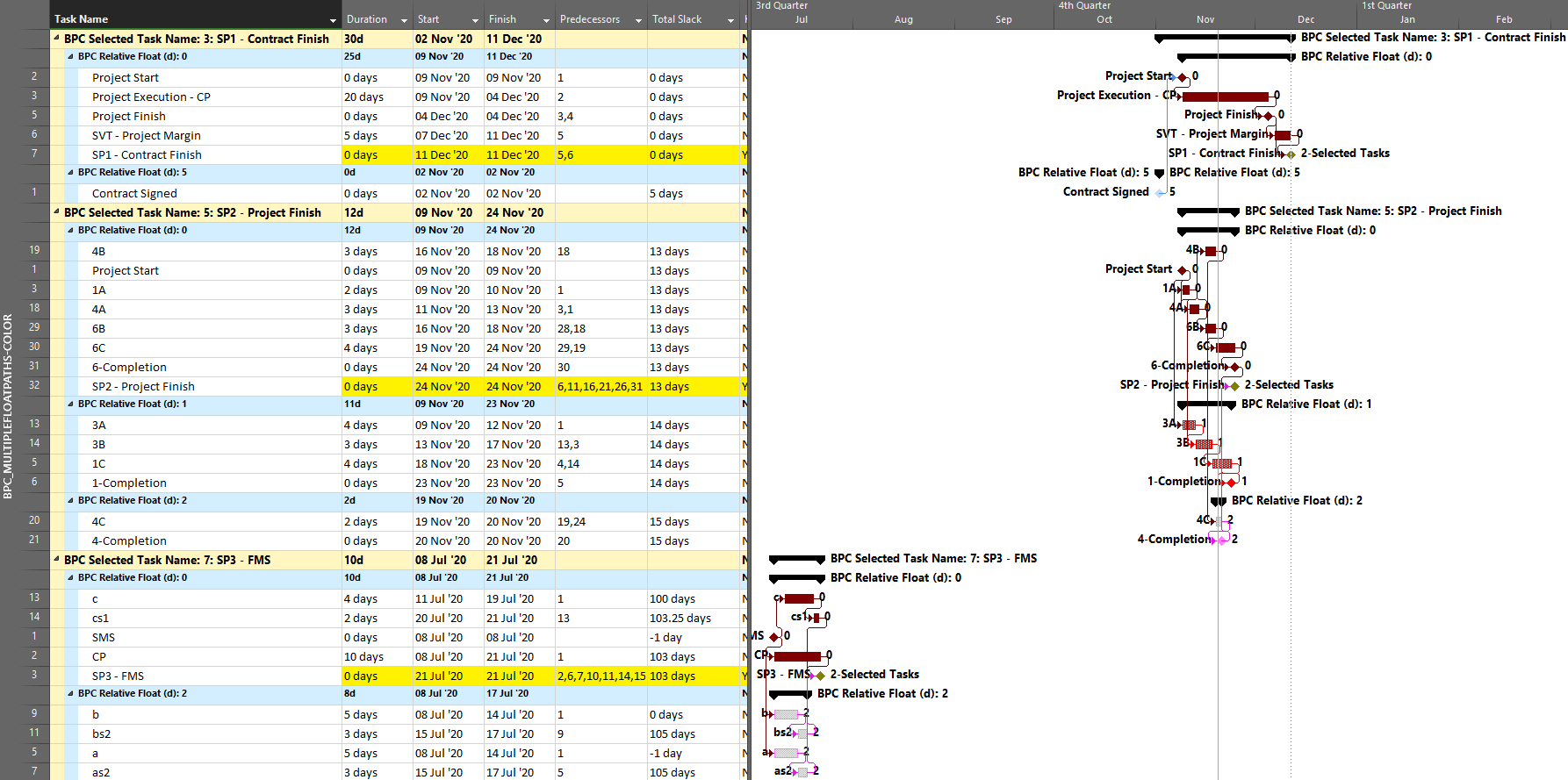

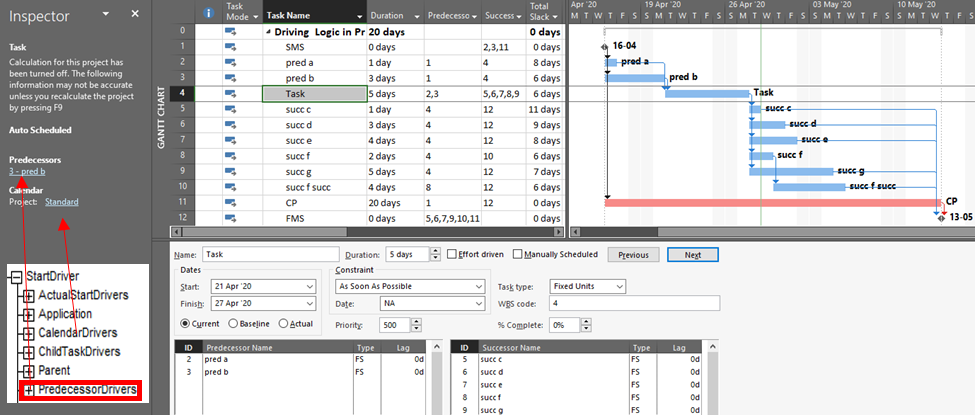

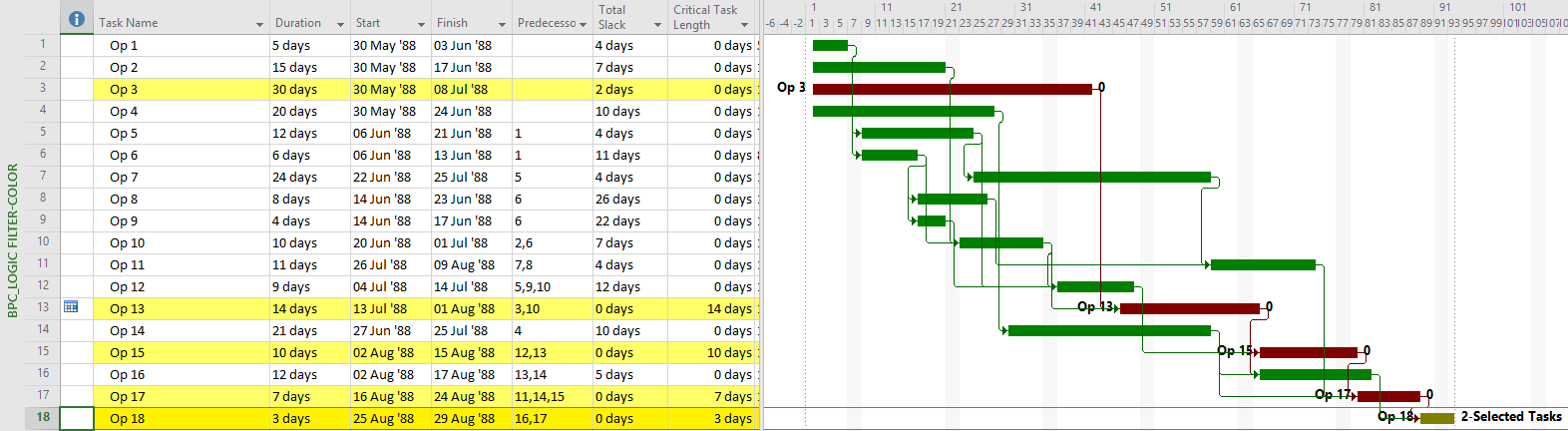

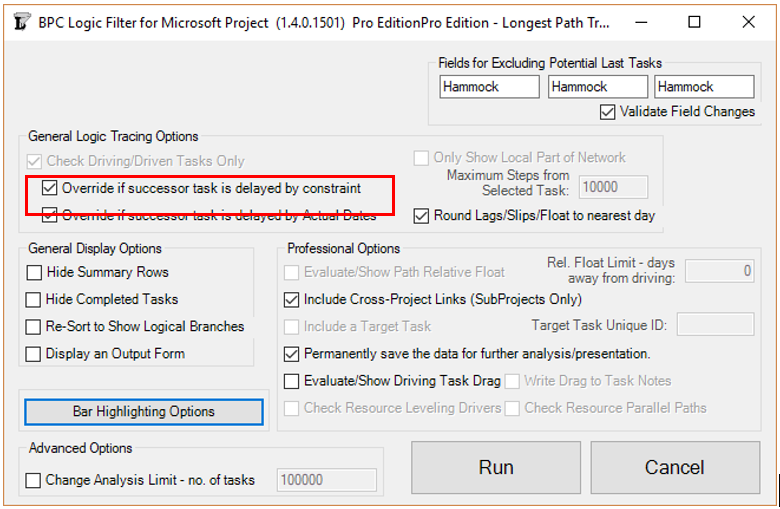

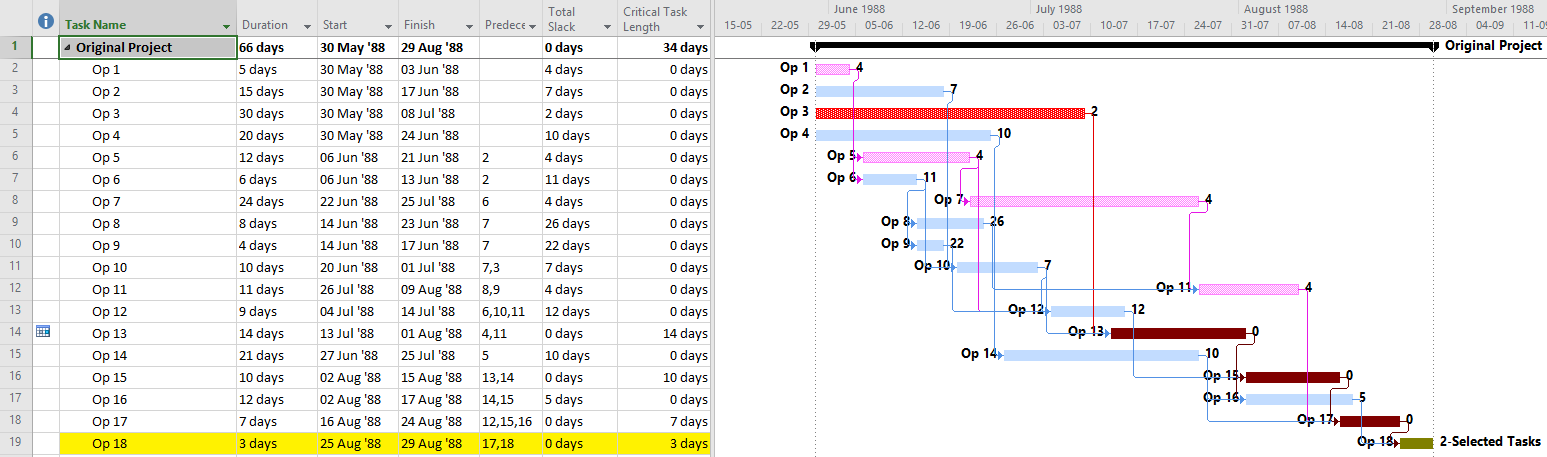

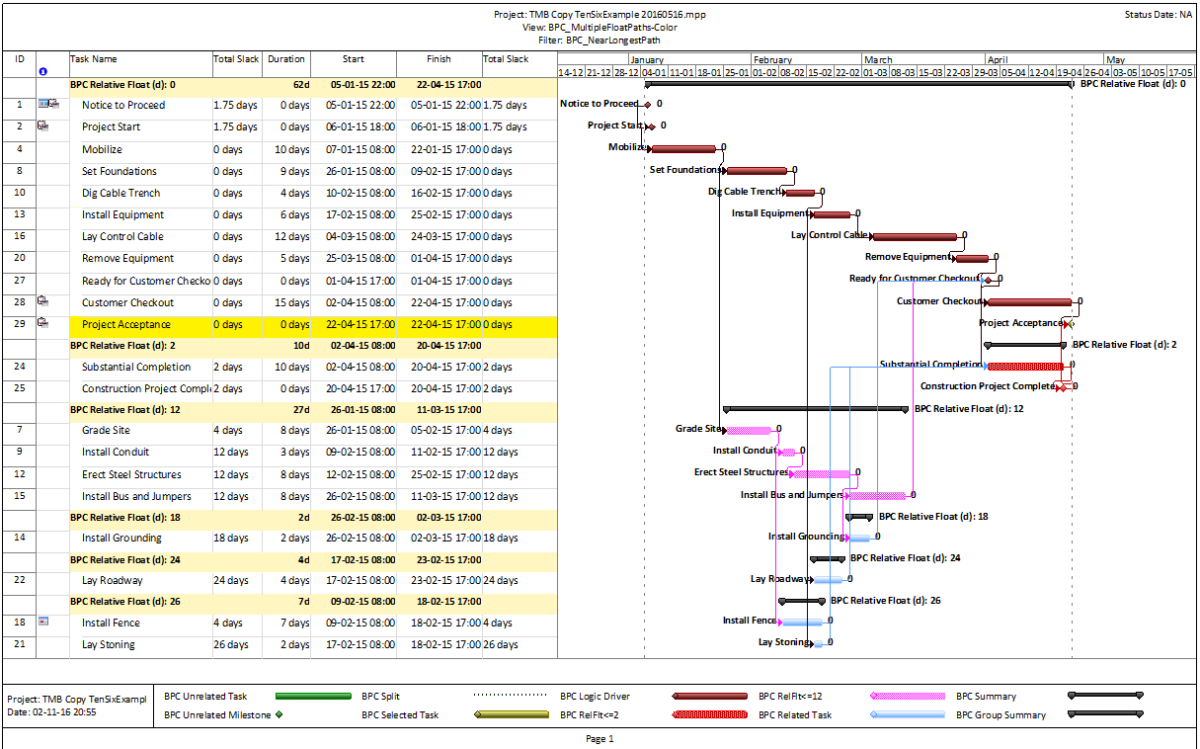

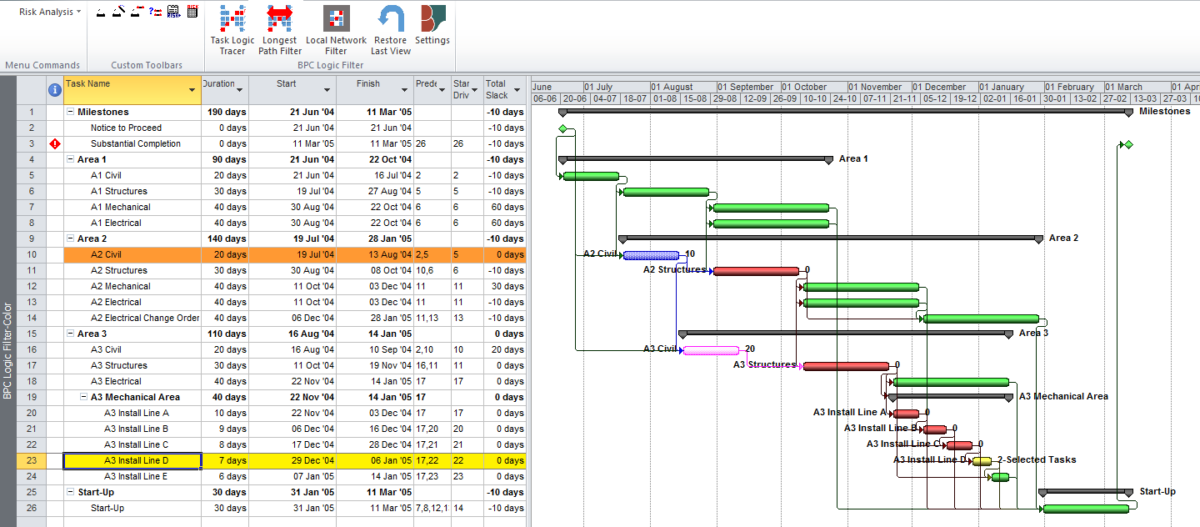

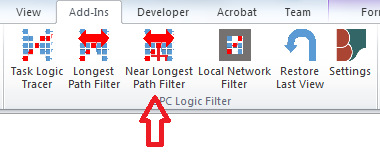

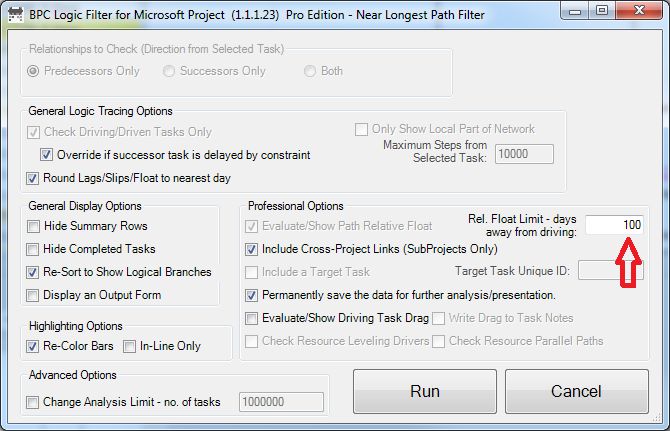

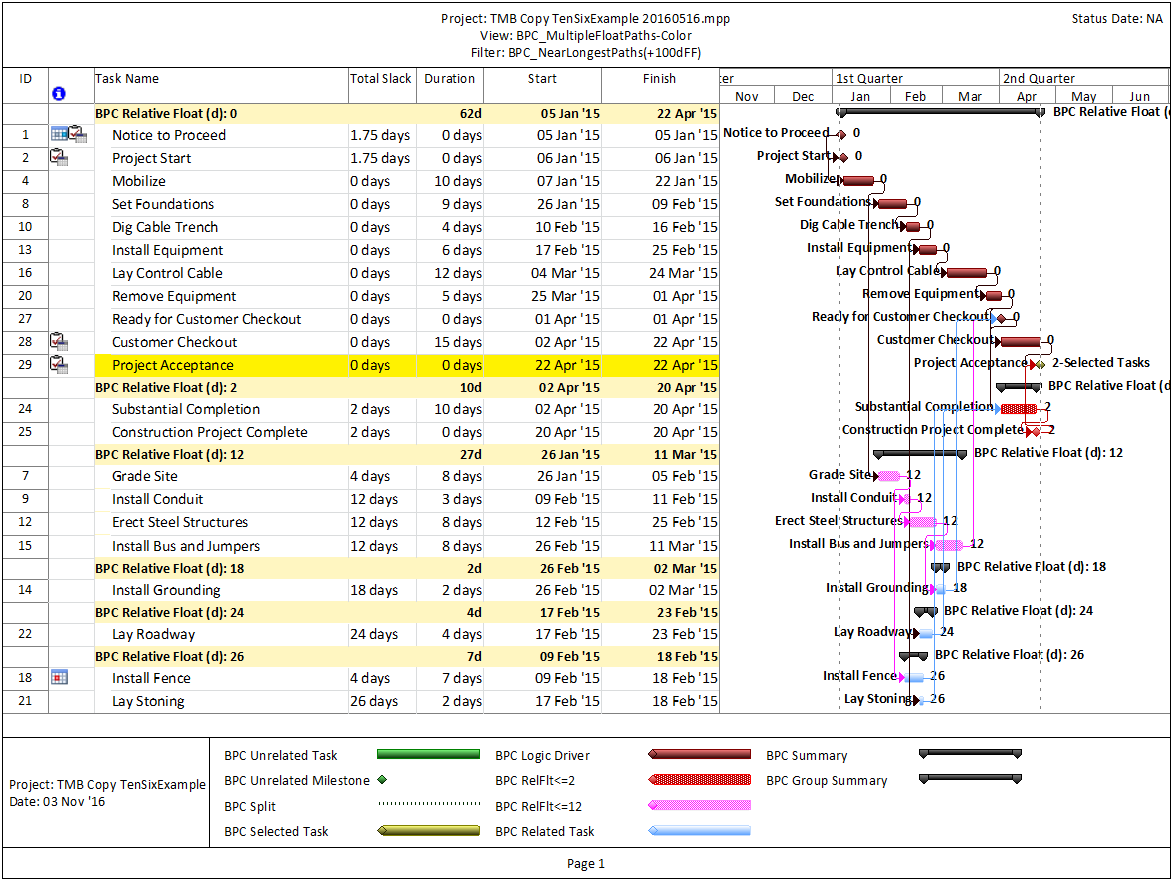

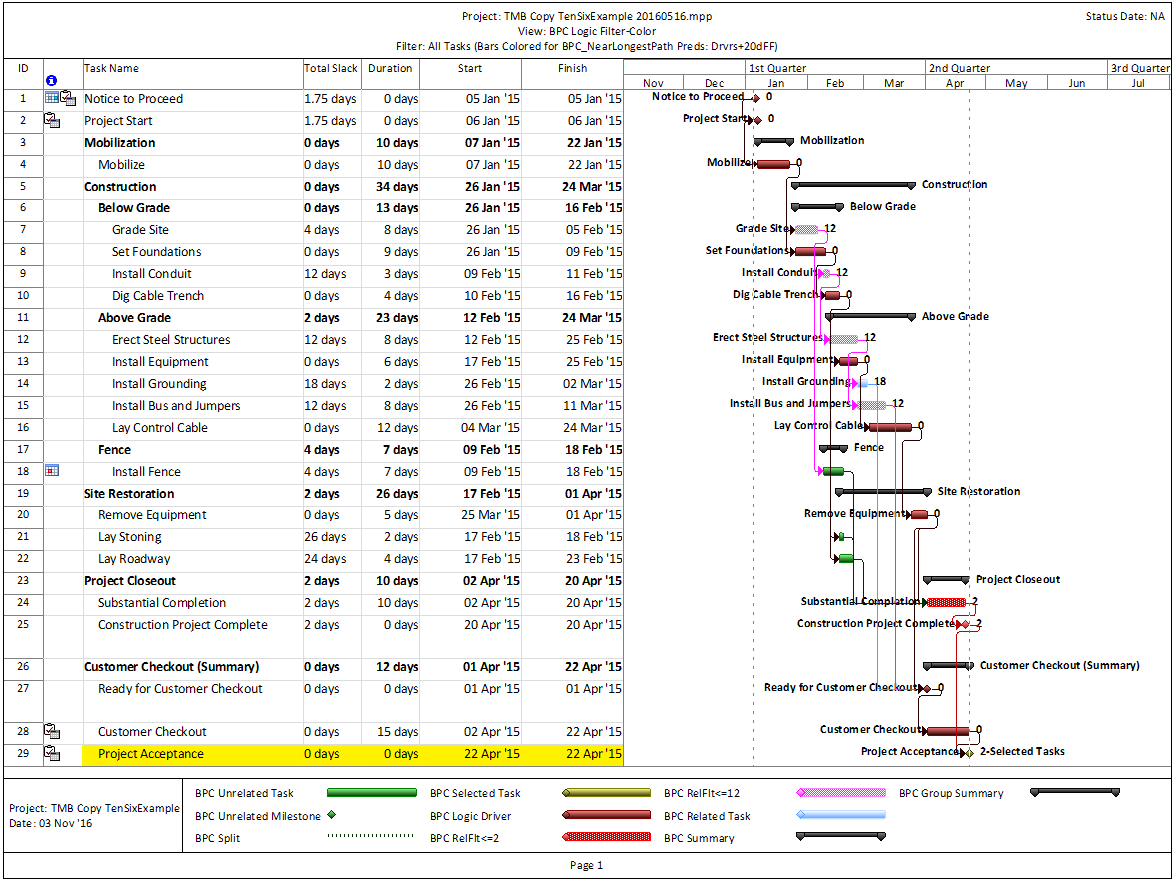

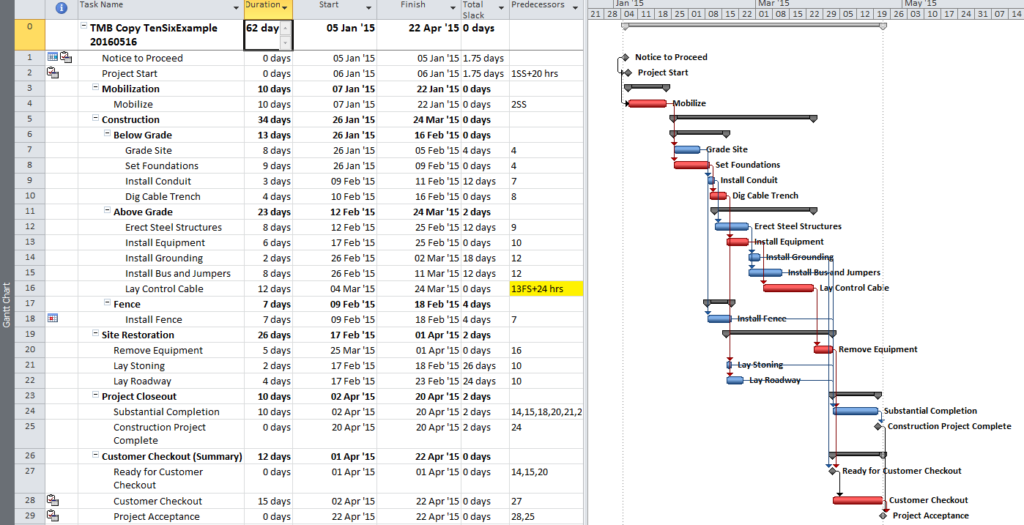

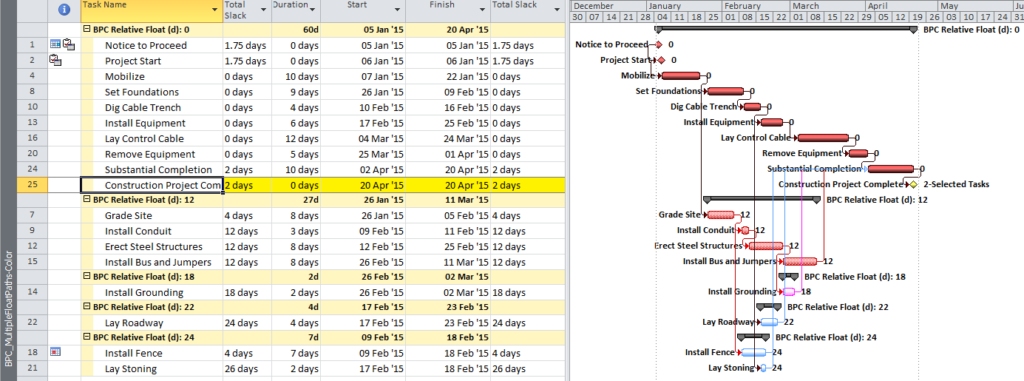

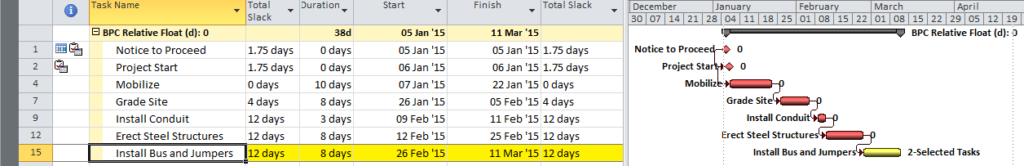

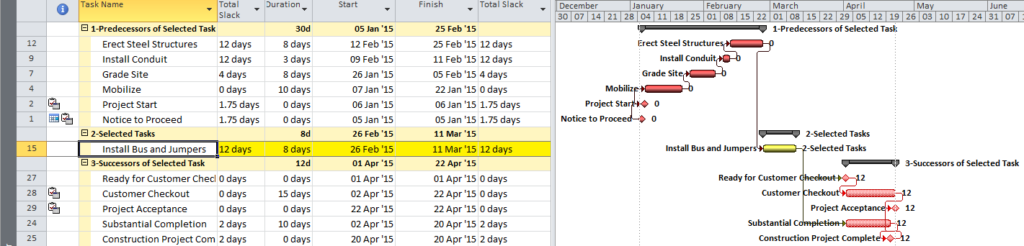

MSP provides no out-of-the-box solutions to address these weaknesses in critical path identification. Total float/slack remains the sole basis for applying the “critical” flag, yet the impacts of constraints, deadlines, and calendars remain unaddressed. In MSP 2013 and later versions, the “task path” bar style modifier does provide a basis for graphically identifying the driving path to a selected completion activity, and this is helpful. Nevertheless, a logic tracing add-in (like the BPC Logic Filter program that I helped to develop) is necessary to correctly identify the controlling schedule logic – including the true critical path – in a complex MSP schedule.

Definitions and Recommended Practices

Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA – 2009)

DCMA’s in-house training course, Integrated Master Plan/Integrated Master Schedule Basic Analysis (Rev 21Nov09) is the source of the “14-Point Assessment” that – because its explicit “trigger” values are easily converted to pass/fail thresholds and red/yellow/green dashboards – is seen as a de-facto industry standard for schedule health assessment. The course materials contain the following definitions:

(Slide 28) Critical Path ~ Sequence of discrete work packages that has the longest total duration through an end point.

~ has the least amount of total float

~ cannot be delayed without delaying the completion date of the contract (assuming zero float).

(Slide 98) Critical Path – Definition: a sequence of discrete tasks/activities in the network that has the longest total duration through the contract with the least amount of float.

~ A contract’s critical path is made up of those tasks in which a delay of one day on any task along the critical path will cause the project end date to be delayed one day (assuming zero float).

(Slide 99) The critical path is ‘broken’ whenever there is not a sequence of connected critical path tasks that goes from the first task of the schedule until the last task. A broken Critical Path is indicative of a defective schedule.

These definitions are mostly (though not entirely) consistent with each other. They do share a common emphasis on the … “longest”… “sequence” … with “lowest total float” and direct transmission of delay from any critical-path task directly to the project’s completion. Obviously, the reliance on total float makes them incompatible with any project schedule that incorporates multiple calendars, late constraints, or resource leveling. Moreover, the description of (and objection to) a broken Critical Path rules out driving paths with discontinuities caused by early date constraints.

(Slide 97) Critical Task: Some tasks possess no float…they are known as critical tasks.

~Any delay to a critical task on the critical path will cause a delay to the project’s end date.

Unlike most of the later definitions, DCMA’s appears to contemplate the existence of critical tasks that are not on the critical path. Obviously, the expectation that such critical tasks possess “no float” is not compatible with negative-float regimes, nor is it compatible with the positive-float regimes that accompany project “must finish by” constraints in P6.

AACE International (2010 & 2018)

AACE International (formerly the Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering) maintains and regularly updates its Recommended Practice No. 10S-90: Cost Engineering Terminology. The most recent issue of RP 10S-90 (June 2018) includes the following definitions:

CRITICAL PATH – The longest continuous chain of activities (may be more than one path) which establishes the minimum overall project duration. A slippage or delay in completion of any activity by one time period will extend final completion correspondingly. The critical path by definition has no “float.” See also: LONGEST PATH (LP). (June 2007)

CRITICAL ACTIVITY – An activity on the project’s critical path. A delay to a critical activity causes a corresponding delay in the completion of the project. Although some activities are “critical,” in the dictionary sense, without being on the critical path, this meaning is seldom used in the project context. (June 2007)

Unfortunately, these definitions fall apart in the presence of early-date constraints, multiple calendars, multiple late-date constraints, or negative total float – when the second and third clauses in both definitions no longer agree with the first. They appear distinctly out of sync with modern project scheduling practices, and (according to AACE International’s Planning and Scheduling Subcommittee Chair) an update is pending.

AACE International’s RP No. 49R-06, Identifying the Critical Path (last revised in March 2010) instead defines the Critical Path as

…the longest logical path through the CPM network and consists of those activities that determine the shortest time for project completion. Activities within this [group (sic)] or list form a series (or sequence) of logically connected activities that is called the critical path.

Aside from the apparently inadvertent omission of a word, I don’t have any problem with this definition. It is certainly better, in my opinion, than the first.

RP 49R-06 notes the existence of “several accepted methods for determining the critical path” and goes on to describe the four “most frequently used” methods:

- Lowest Total Float. This is as I described under Workarounds for Total Float Criteria, above. Although this method is listed first, the RP spends four pages detailing the issues that make total float unreliable as a CP indicator. As long as the CP is to be defined only with respect to the most urgent constraint in the schedule (including the finish reflection) – and there are no calendar issues – then this method provides a useful result.

- Negative Total Float. In apparent acquiescence to the limitations of MSP, the RP describes this method by first abandoning the fundamental definition of the critical path as a specific logic path. It then allows the “critical” classification for any activity that must be accelerated in order to meet an applied deadline or constraint. Ultimately, the RP attempts to justify this method based solely on certain legal/contractual considerations of concurrent delay. It is not useful for those whose primary interest is timely completion of the project, or a particular part of the project, using critical path management principles.

- Longest Path. This “driving path to project completion” algorithm, as I described above in Workarounds for Total Float Criteria, has been implemented in versions of (Oracle) Primavera software since P3 (2.0b). It is the preferred method for P6 schedules with constraints and/or multiple activity calendars. A similar algorithm is included in BPC Logic Filter, our add-in for Microsoft Project. While the method is nominally aimed at finding the driving path(s) to the last activity(ies) in the schedule, it can be combined with other techniques (namely a super-long trailing dummy activity) to derive the driving path to any specific activity, e.g. a specific “substantial completion” or “sectional-completion” milestone.

- “Longest Path Value.” This is an expanded method for identifying the driving and near-driving paths to project completion. The method works by adding up relationship floats leading to a specific substantial completion milestone. If the aggregate value of these floats along a specific logic path (i.e. “Longest Path Value”) is zero, then that path is identified as the critical path. While the RP suggests that this method can be performed manually (presumably by “click-tracing” through the network of a P6 schedule), manual implementation in complex schedules is tedious and error prone. As implemented in Schedule Analyzer Software, this method is essentially an improved version of P6’s Longest Path method (except that the add-in cannot change the “critical” flag for activities.) It is a preferred method in P6 for those possessing the Schedule Analyzer Software. BPC Logic Filter performs similar analyses – using “path relative float” instead of “Longest Path Value” – for MSP schedules.

While not listed among the “most frequently used” methods, P6’s MFP analysis option is briefly addressed by the RP in the context of identifying near-critical paths. BPC Logic Filter performs similar analyses for MSP schedules.

None of the four methods described are useful for identifying the resource critical path (or resource-constrained critical path) of a leveled schedule.

Project Management Institute (PMI-2011)

PMI’s Practice Standard for Scheduling (Second Edition, 2011) explicitly defines the critical path as…

Generally, but not always, the sequence of schedule activities determining the duration of the project. Generally, it is the longest path through the project. However, a critical path can end, as an example, on a schedule milestone that is in the middle of the schedule model and that has a finish-no-later-than imposed date schedule constraint.

Unlike the RP (49R-06) from AACE International, PMI’s Practice Standard provides no meaningful method for quantitatively identifying the activities of the critical path (or any logic paths) in a particular schedule model. In fact, in its description of the precedence diagram method (PDM – the modern version of CPM used by most modern scheduling software) the Practice Standard acknowledges the complicating factors of constraints and multiple calendars but notes that “today’s computerized scheduling applications complete the additional calculations without problems.” Then it concludes, “In most projects the critical path is no longer a zero float path, as it was in early CPM.” The Practice Standard goes on to scrupulously avoid any explicit link between total float and the critical path. The impact of all this is to just take the software’s word for what’s “critical” and what isn’t. That’s not particularly helpful.

Finally, educating senior stakeholders on the subtle difference between “schedule critical” and “critical” is always one of the first issues faced when implementing systematic project management in non-project focused organizations. The Practice Standard’s several conflicting definitions of critical activities tend to confuse rather than clarify this distinction.

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO-2015)

The GAO’s Schedule Assessment Guide: Best Practices for Project Schedules (GAO-16-89G, 2015) has been taken to supersede the earlier DCMA internal guidance in many formal uses. (Nevertheless, the GAO’s decision to discard any formal trigger/threshold values – a good decision in my view – means that the DCMA-based assessments and dashboards remain popular.) The GAO document contains the following formal definitions:

Critical path: The longest continuous sequence of activities in a schedule. Defines the program’s earliest completion date or minimum duration.

[With some minor reservations related to meaning of “longest,” I believe this is a good definition.]

Critical activity: An activity on the critical path. When the network is free of date constraints, critical activities have zero float, and therefore any delay in the critical activity causes the same day-for-day amount of delay in the program forecast finish date.

[Unfortunately, the caveats after the first clause are insufficient, ignoring the complicating effects of multiple calendars.]

For the most part – and despite the float-independent formal definition above – the Schedule Assessment Guide’s “Best Practices” tend to perpetuate continued reliance on total float as the sole indicator of the critical path. In fact, “Best Practice 6: Confirming That the Critical Path Is Valid” does a good job of illustrating the complicating factors of late constraints and multiple calendars, but this review leads essentially to the differentiation of “critical path” (based on total float alone) from “longest path” (based on driving logic). This is a direct contradiction of the formal definition above. In general, the text appears to be written by a committee comprised of P6 users (with robust driving/Longest Path analysis tools) and MSP users (without such tools.) Thus, for every “longest path is preferred,” there seems to be an equal and opposite, “the threshold for total float criticality may have to be raised.” This is silly.

National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA-2016)

The NDIA’s Integrated Program Management Division has maintained a Planning & Scheduling Excellence Guide (PASEG), with Version 3.0 published in 2016. The PASEG 3.0 includes the following key definitions:

Critical Path: The longest sequence of tasks from Timenow until the program end. If a task on the critical path slips, the forecasted program end date should slip.

Driving Path(s): The longest sequence of tasks from Timenow to an interim program milestone. If a task on a Driving Path slips, the forecasted interim program milestone date should slip.

The second clause of each definition – which presumes a single calendar – is included in the Schedule Analysis chapter but is excluded from the formal definition in Appendix A. Timenow is effectively the data/status date. The PASEG does not define or mention critical task/activity as distinct from a “task on the critical path.”

The PASEG notes, “Some of the major schedule software tools have the ability to identify and display critical and driving paths. Additionally, there are many options available for add-in/bolt-on tools that work with the schedule software to assist in this analysis.” [I suppose BPC Logic Filter would be one of the mentioned add-in tools for Microsoft Project.]

The PASEG also mentions some manual methods for identifying critical and driving paths, e.g.:

a. Imposing a temporary, super-aggressive late constraint and grouping/sorting the output (presumably by total float and early start. Though not explicitly mentioned in the method description, total float is the key output affected by the imposed constraint.) Obviously, this method isn’t reliable when more than one calendar is used.

b. Building a custom filter by manually “click-tracing” through driving logic and marking the activities. This method is most reliable in P6, with some caveats. It is reliable in MSP only under some fairly restrictive conditions.

In general, these methods are non-prescriptive, though the emphasis on driving logic paths (rather than total float) seems clear.

Guild of Project Controls (GPC, “The Guild” – 2018)

The Guild is a relatively young (~2013) international community of project controls practitioners – initially associated with the PlanningPlanet.com web site – whose founding members have assembled a Project Controls Compendium and Reference (GPCCaR). The GPCCar takes the form (more or less) of an introductory training course on Project Controls, including Planning and Scheduling. The GPCCaR includes no formal Glossary, Terminology, or Definitions section, so “critical path” and “critical path activities” accumulate several slightly varying definitions in the applicable Modules (07-01, 07-7, and 07-8). In general, “zero total float” and “critical path” are used interchangeably, and the complications of multiple calendars and multiple constraints in P6 and MSP are ignored. This is not a suitable reference for complex projects that are scheduled using these tools.

American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE)

ASCE Standard ANSI/ASCE/CI 67-17 – Schedule Delay Analysis is one of the few documents with a clear and correct distinction between the critical path and the collection of critical activities:

Critical path—The series of logically connected tasks that define the minimum overall duration for completion of the project, also known as the longest path. There can be more than one critical path in the schedule.

Critical activities—Activities with zero or negative float in a schedule reflecting a current adjusted completion date, some of which may not be on the critical path.

Recap

- A full understanding of driving and non-driving schedule logic paths for major schedule activities is useful for managing and communicating a project execution plan.

- The most important logic path in the project schedule is the “critical path,” i.e. the driving path to project completion. Overall acceleration (or recovery) of a project is only made possible by first shortening the critical path. Acceleration of activities that are not on the critical path yields no corresponding project benefit to project completion. Multiple critical paths may exist.

- Some traditional notions of critical path path attributes – e.g. critical path activities possess no float; slippage or acceleration of critical path activities always translates directly to project completion – are not reliable in modern project schedules.

- Total float remains a valuable indicator of an activity’s scheduling flexibility with respect to completion constraints of the project. An activity with TF=0 may not be allowed to slip if all project completion constraints are to be met. Activities with TF<0 must be accelerated if all the constraints are to be met.

- Project scheduling software typically defines individual activities as “critical” without fully accounting for common complicating factors like multiple constraints and calendars. As a result, the collection of “critical” tasks/activities in a complex project schedule often fails to identify a true critical path.

- A critical task/activity is best defined (in my opinion) as either:

- An activity that resides on the critical path; or

- An activity whose delay will lead to unacceptable delay of the project completion; or

- An activity whose delay will lead to unacceptable delay of some other constrained activity or milestone.

- In general, these conditions are mutually exclusive, and different activities within a single project schedule may satisfy one or more of them.

- Professional project managers and schedulers should be careful not to automatically characterize “critical” tasks (i.e. those with low total float) as indicators of a project’s critical path when complicating factors are present.